10 Things to Know about Medicaid Managed Care

Managed care plays a key role in delivering health care services to Medicaid participants. With 69% of Medicaid beneficiaries participating in comprehensive managed care plans nationwide, plans play a vital role in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and in the tax implications for states. This letter describes 10 key issues related to the deployment of comprehensive, risk-based managed care in the Medicaid program, and details data and trends related to MCO enrollment, the development of actuarial MCO capitation payments, service carve-ins, the state as a whole and the state highlighted spending on MCOs, MCO parent companies, access to care workers, and government and planned activities related to quality, value-based payments, and the social determinants of health. Understanding these trends provides important context for the role MCOs play in the Medicaid program as a whole and during the current COVID-19 public health emergency and associated economic downturn.

1. Today, surrendered managed care is the predominant way states provide services to Medicaid participants.

States design and manage their own Medicaid programs under federal regulations. States determine how they provide and pay for Medicaid beneficiary services. Almost all countries have some form of managed care – comprehensive risk-based managed care and / or primary care case management (PCCM) programs. As of July 2019, 40 states, including DC, have signed comprehensive, risk-based managed care plans to care for at least some of their Medicaid beneficiaries (Figure 1). Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) provide Medicaid beneficiaries with comprehensive acute care and, in some cases, long-term services and support. MCOs accept a monthly payment per member per month for these services and are at financial risk for the Medicaid services identified in their contracts. States have entered into risk-based managed care plan contracts for a variety of purposes to improve budget predictability, cut Medicaid spending, improve access to care and value, and meet other goals. While the move to MCOs has improved budget predictability for states, the evidence of the impact of managed care on access to care and costs is limited and inconsistent.

Figure 1: As of July 2019, 40 states were using capitalized managed care models to deliver services in Medicaid

2. States develop MCO capitalization rates each year, which must be actuarially sound and may include risk mitigation strategies.

States pay Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) one rate per member per month for the Medicaid services specified in their contracts. Federal law requires payments to Medicaid MCOs to be actuarially sound. Actuarial soundness means that "the capitalization rates are expected to provide for all reasonable, reasonable, and achievable costs required under the terms of the contract and for the operation of the managed care plan for the period and the eligible population of the contract." to FFS (Fee-for-Service), Capitation offers fixed payments in advance for plans for expected utilization of covered services, administration costs and profits. The plan rates are usually set for an evaluation period of 12 months and must be reviewed and approved by CMS each year. States can employ a variety of mechanisms to adjust plan risk, incentivize plan performance, and ensure payments are not too high or too low, including risk-sharing agreements, risk and severity adjustments, medical loss ratios (MLRs), or incentive – and source agreements.

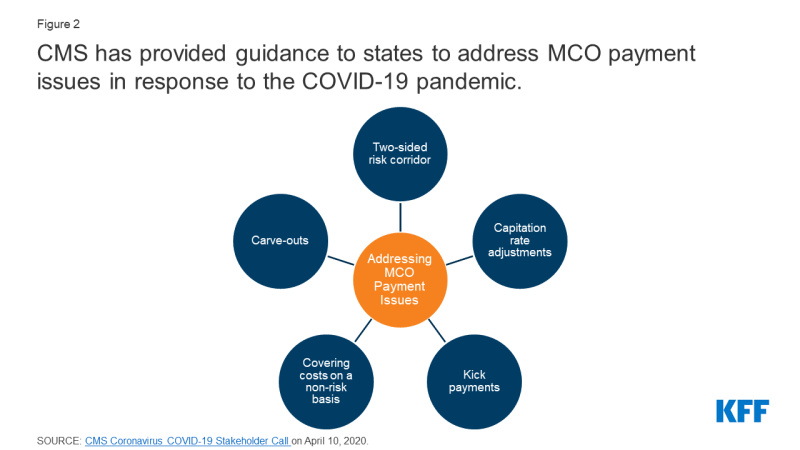

The current MCO capitation rates may have been developed and implemented before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, these rates may not include costs for COVID-19 tests and treatments. At the same time, the uptake of non-urgent measures has decreased as individuals seek to limit the risk / exposure of contracting the coronavirus. As a result, many states are exploring options to adjust existing MCO rates and risk-sharing mechanisms in response to unexpected COVID-19 costs and conditions that have resulted in lower utilization. Under the existing Medicaid Managed Care agency, states have various options to resolve payment problems that have arisen as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic. CMS has outlined government options to change managed care contracts and rates in response to COVID-19, including risk mitigation strategies, adjusting capitalization rates, covering COVID-19 costs on a non-risk basis, and outsourcing costs associated with COVID-19 from MCO contracts (Figure 2). These options vary widely in terms of implementation / operational complexity, and all options require CMS approval. In addition, there is still great uncertainty about the impact of the pandemic on managed care funding / rates, especially in the current plan rating periods (which usually run on a calendar year or state fiscal year basis) as it is still too early Knowing this when there is pent-up demand that can drive utilization up as the pandemic wears off, as well as unknowns about where / when COVID-19 cases and related costs will increase as the pandemic progresses.

Figure 2: CMS has provided guidance to states on how to resolve MCO payment issues in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

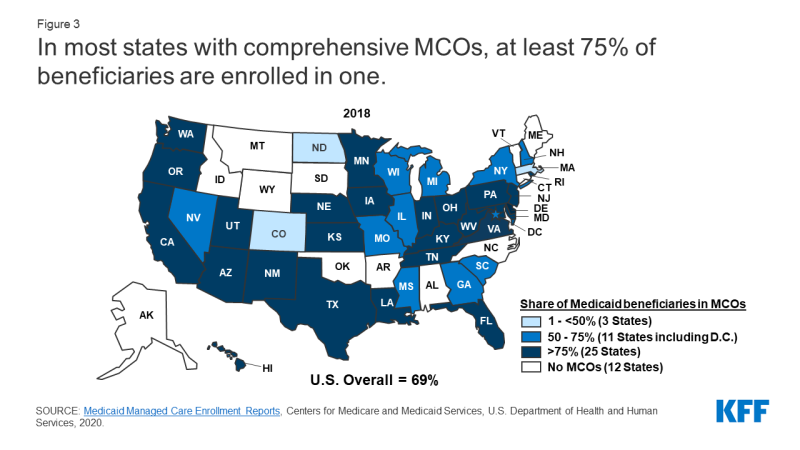

3. As of July 2018, more than two-thirds (69%) of all Medicaid beneficiaries were receiving care from comprehensive risk-based MCOs.

As of July 2018, 53.9 million Medicaid participants were served through risk-based MCOs. 25 MCO countries covered more than 75% of Medicaid beneficiaries in MCOs (Figure 3).

Figure 3: In most states with comprehensive MCOs, at least 75% of beneficiaries are enrolled in one

4. Children and adults are more often enrolled in MCOs than seniors or people with disabilities. However, states are increasingly including beneficiaries with complex needs in MCOs.

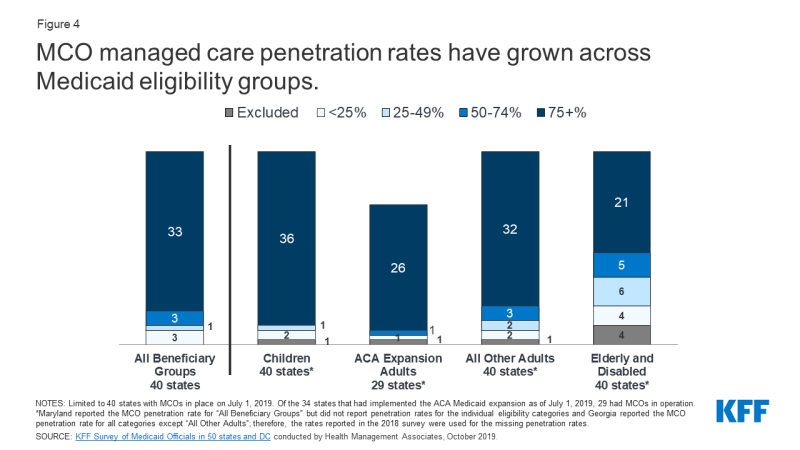

As of July 2019, 36 MCO countries stated that they covered 75% or more of all children with MCOs (Figure 4). Of the 34 states that implemented the ACA Medicaid extension in July 2019, 29 used MCOs to cover newly eligible adults, and the vast majority of those states covered more than 75% of beneficiaries in that group through MCOs. Thirty-two MCO states reported MCOs covered 75% or more of low-income adults in pre-ACA expansion groups (e.g. parents, pregnant women). In contrast, only 21 MCO states reported covering 75% or more of the elderly and people with disabilities. Although this group is still less likely to be enrolled in MCOs than children and adults, states have moved over time to include seniors and people with disabilities in MCOs.

Figure 4: MCO Managed Care penetration rates have increased across all Medicaid stakeholders

5. In recent years, many states have received behavioral health services, pharmacy services, and long-term services and support for MCO contracts.

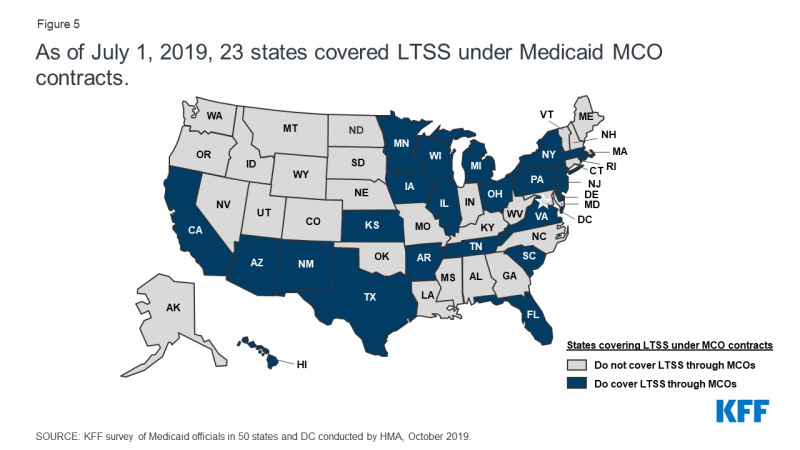

Although MCOs offer full services to beneficiaries, states may elaborate certain services from MCO contracts for fee-for-service (FFS) systems or plans for limited benefits. Services commonly elaborated include behavioral health, pharmacy, dentistry, and long-term services and support (LTSS). However, there has been significant movement between states to incorporate these services into MCOs. As of July 2019, 23 states covered LTSS through Medicaid MCO agreements for at least some LTSS populations (Figure 5).

Figure 5: As of July 1, 2019, 23 states covered LTSS under Medicaid's MCO contracts

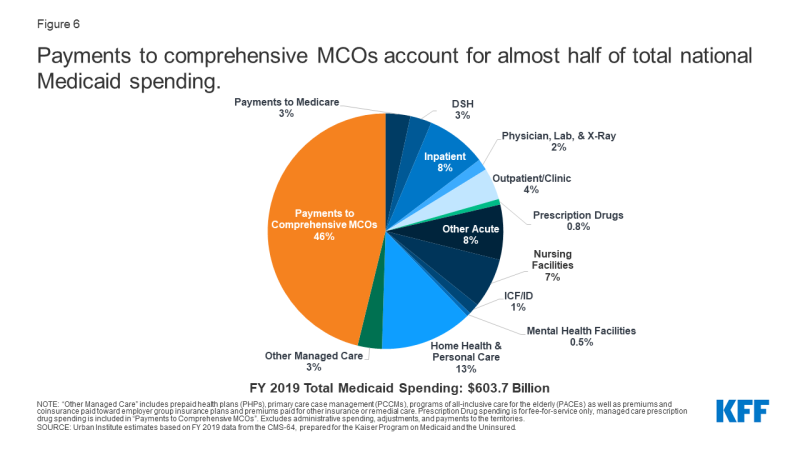

6. In fiscal 2019, payments to large risk-based MCOs made up the bulk of Medicaid spending.

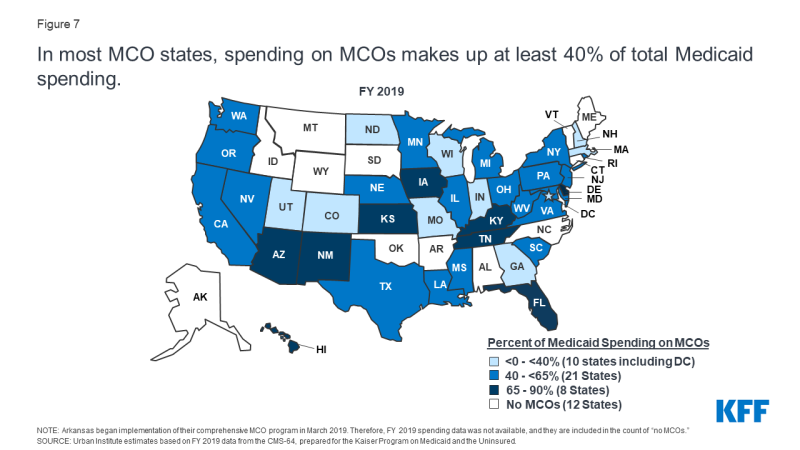

In fiscal 2019, state and federal spending on Medicaid services was nearly $ 604 billion. Payments to MCOs accounted for approximately 46% of total Medicaid spending (Figure 6). The percentage of Medicaid spending on MCOs varies by state, but about three-quarters of MCO states have spent at least 40% of the total Medicaid dollar making payments to MCOs (Figure 7). The MCO's share of spending ranged from 0.4% in Colorado to 87% in Kansas. State-to-state differences reflect many factors including the proportion of the state Medicaid population enrolled in MCOs, the health profile of the Medicaid population, whether they are high-risk or high-cost beneficiaries (e.g., people with disabilities , dual entitled beneficiaries) are included in the MCO registration or excluded from the MCO registration and whether or not long-term services and support are included in MCO contracts. As states expand Medicaid-administered care to include more needy, more costly beneficiaries, expensive long-term services and support, and adults who are new to Medicaid under the ACA, the proportion of Medicaid dollars given to MCOs will continue to grow .

Figure 6: Payments to large MCOs account for nearly half of total national Medicaid spending

Figure 7: In most MCO countries, spending on MCOs accounts for at least 40% of total Medicaid spending

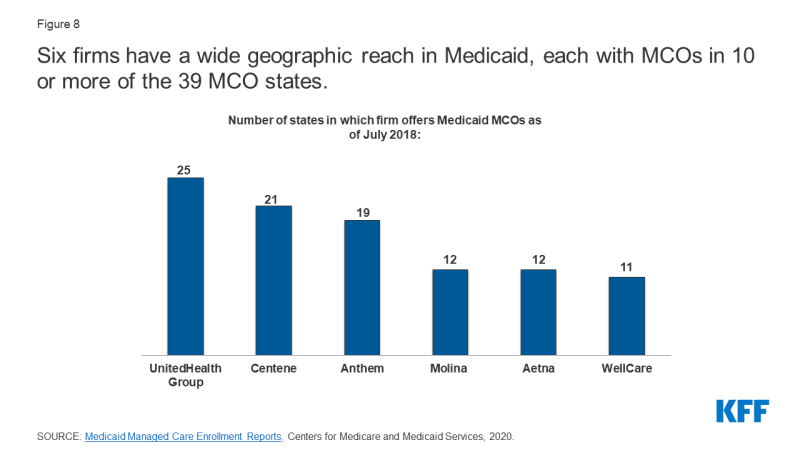

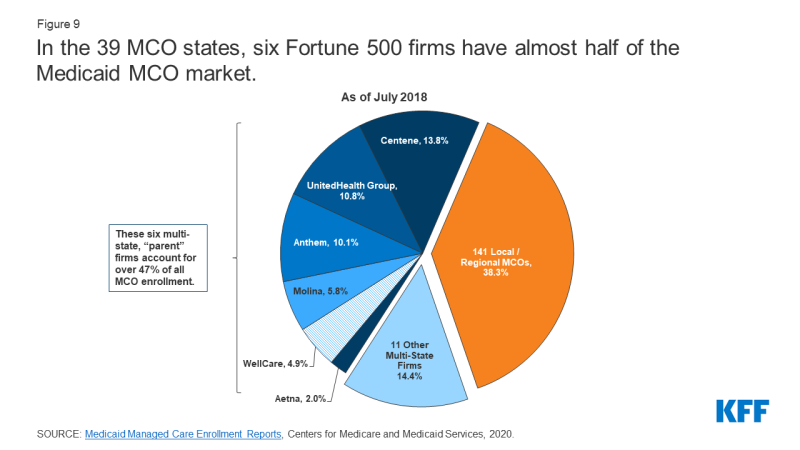

7. A number of major health insurers are heavily involved in the Medicaid managed care market.

The states signed contracts with a total of 290 Medicaid MCOs in July 2018. MCOs are a mix of private for-profit, private not-for-profit, and government plans. As of July 2018, a total of 17 companies were operating Medicaid MCOs in two or more states (called "parent companies"), and these companies accounted for nearly 62% of enrollments in 2018 (Figure 9). Of the 17 parent companies, eight are publicly traded, for-profit companies, while the remaining nine are not for profit. Six companies – UnitedHealth Group, Centene, Anthem, Molina, Aetna and WellCare – have MCOs in 10 or more states (Figure 8) and accounted for over 47% of all Medicaid MCO registrations (Figure 9). All six are listed Fortune 500 companies.

Figure 8: Six companies have a large geographic reach in Medicaid, each with MCOs in 10 or more of the 39 MCO countries

Figure 9: In the 39 MCO countries, six Fortune 500 companies account for nearly half of the Medicaid MCO market

8. Often within general federal and state regulations, the plan is discretionary as to how to ensure access to care for enrolled persons and how to pay providers.

Planning efforts to recruit and maintain your provider networks can play a critical role in determining subscriber access to maintenance through factors such as travel times, waiting times, or the choice of provider. Federal regulations require states to set standards for the adequacy of the network. States have a great deal of flexibility in defining these standards. The final rule for CMS Medicaid Managed Care 2016 included specific parameters for states in setting network adequacy standards, although the regulations proposed by the Trump administration in 2018 would relax those requirements. KFF conducted a survey on Medicaid Managed Care plans in 2017 and found that the response plans listed various strategies for resolving network problems from providers, including direct contact with providers, financial incentives, automatic assignment of members to PCPs, and policies for instant payment. Despite employing different strategies, the plans reported more challenges in recruiting specialty providers than in recruiting basic service providers on their networks. These challenges were due more to supplier bottlenecks than to the low level of supplier involvement in Medicaid.

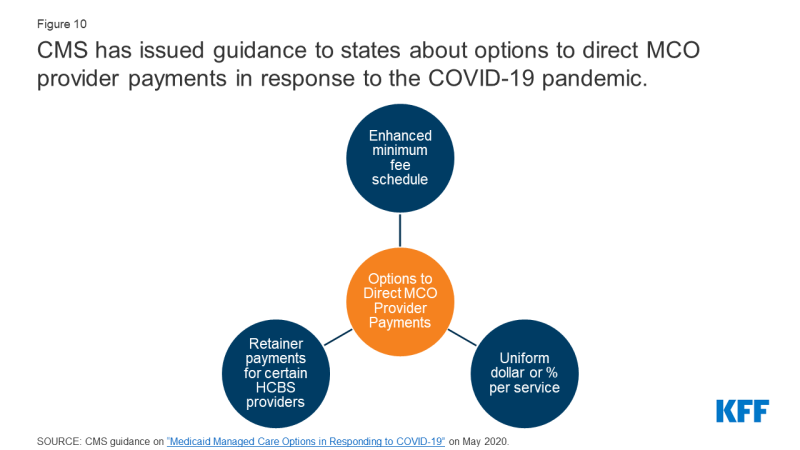

To ensure participation, many states require minimum provider tariffs in their contracts with MCOs, which may be tied to service fees. In a 2019 KFF survey of Medicaid directors, about half of MCO states said they have minimum reimbursement rates for providers in their MCO contracts for inpatient hospitals, outpatient hospitals, or general practitioners. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many Medicaid providers may face tax burdens and significant lost revenue. For providers in states that have heavily reliant on managed care, states make payments to plans, but these funds may not go to providers who have had decreased utilization. As a result, states are evaluating options and flexibility within the existing managed care rules to direct / bolster payments to Medicaid providers and maintain access to care for subscribers. States can require managed care plans to make payments to their network providers using CMS-approved methodologies to meet other state goals and priorities, including responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, states could require plans to introduce a uniform temporary increase in payment amounts per provider for services covered by the managed care contract, or states could combine different state-directed payments to temporarily increase provider payments (Figure 10) .

Figure 10: CMS has issued guidance to states on options for routing payments from MCO providers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

9. Over time, the expansion of risk-based managed care in Medicaid has been accompanied by an increased focus on measuring quality and outcomes.

Almost all MCO countries stated that they had used at least one selected quality initiative for managed care from Medicaid in the 2019 financial year (Figure 11). More than three quarters of MCO countries (34 out of 40) said they had taken initiatives in fiscal 2019 to make MCO comparative data publicly available (compared to 23 countries in 2014). More than half of MCO countries reported agreements on withholding capital (24 out of 40) and / or paying performance incentives (25 out of 40) in fiscal 2019. States using compensation for performance bonus or penalty, withholding funds, and / or performance report on the Auto Allocation Quality Score, which links these quality initiatives to a variety of focus areas for performance measurement. Over three-quarters of the MCO countries (31 states) reported using chronic disease management metrics to reward or punish plan performance (Figure 11). More than half of the MCO countries reported linking quality initiatives with perinatal / birth outcome measurements (26 states) or mental health measures (24 states). These priorities are not surprising given the chronic physical health and behavioral needs of the Medicaid population, as well as the significant proportion of Medicaid-funded births in the country. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, states may need to revise the provisions of the MCO Treaty, including requirements for quality measurement, as the pandemic is likely to impact clinical practice and timely reporting of quality data.

Figure 11: States implement a range of quality initiatives under MCO contracts and link these initiatives to a variety of focus areas for performance measurement

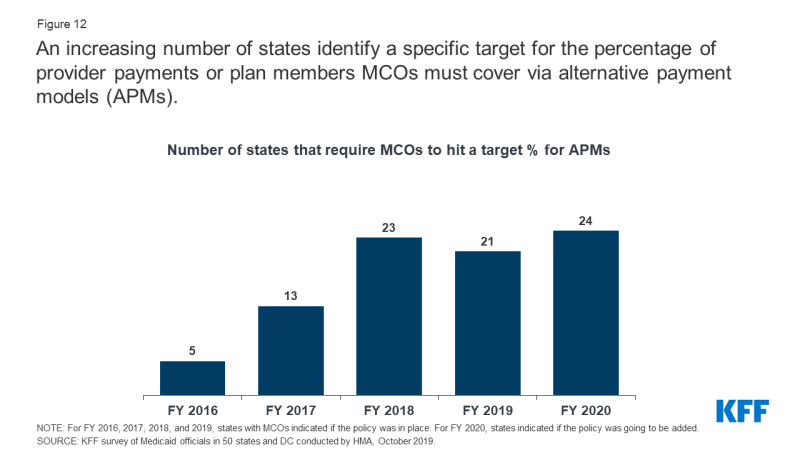

Alternative Payment Models (APMs) are replacing FFS / Volume Driven Vendor Payments with payment models that incentivize quality, coordination, and value (e.g., shared savings / risk sharing and episode-based payments). More than half of the MCO countries (21 out of 40) set a target percentage in their MCO contracts for the percentage of payments from providers, network providers or plan members that MCOs must cover via alternative payment models in fiscal year 2019 (Figure 12). Several states reported that their APM goals were tied to the Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network (LAN) APM framework, which categorizes APMs into levels. The 2017 KFF survey of Medicaid Managed Care plans found that nearly all response plans use at least one alternative payment model for at least some providers. The vast majority of plans use incentives and / or bonus payments that are tied to performance metrics. Fewer plans have been reported that use pooled or episode-based payments or shared savings and risk arrangements.

Figure 12: More and more states are identifying a specific target for the percentage of provider payments or plan members that MCOs must cover through alternative payment models (APMs).

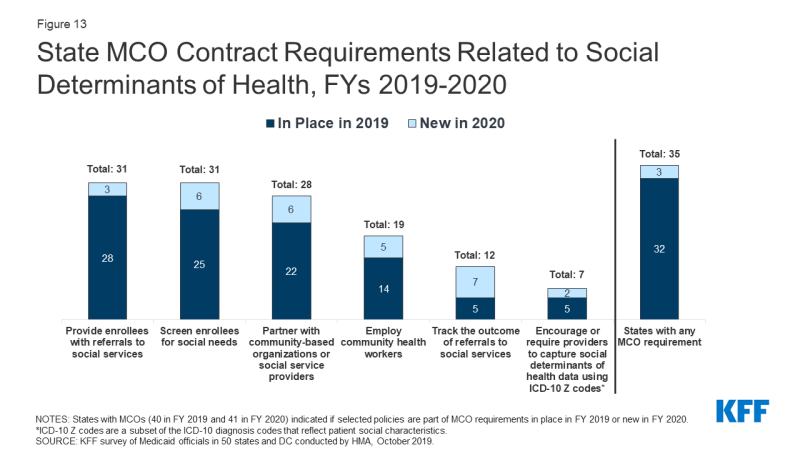

10. States seek strategies from Medicaid MCOs to identify and address social determinants of health.

Many states use MCO treaties to promote strategies to combat social determinants of health. For fiscal 2020, over three-quarters (35 states) of 41 MCO states said they were using Medicaid MCO contracts to promote at least one strategy to combat social determinants of health (Figure 13). For fiscal 2020, around three-quarters of MCO states stated that MCOs are required to screen participants for social needs (31 states). Referral of subscribers to social services (31 states); or partnerships with community-based organizations (28 states). Almost half of the MCO states reported requiring MCOs to hire community health workers (CHWs) or other non-traditional health workers (19 states). The 2017 KFF survey of Medicaid Managed Care plans found that the majority of the plans were actively working to help beneficiaries connect to social services related to housing, nutrition, education, or employment.

Figure 13: State MCO contract requirements related to social determinants of health, FY 2019-2020

Although federal reimbursement rules prohibit spending on most non-medical services, plans can use administrative savings or government funds to provide these services. “Value-added services” are additional services outside of the covered contractual services and are not considered to be a covered service in the sense of determining the capitalization rate. In a 2020 KFF survey of Medicaid directors, MCO states reported a number of programs, initiatives, or value-added services that MCOs were launching in response to the COVID-19 emergency. The most frequently mentioned offerings and initiatives were food aid and home-delivered meals (11 states), and improved MCO care management and contact efforts, often targeting those at high risk for COVID-19 infection or complications, or those who who tested positive for COVID-19 (8 states). Other examples include states that have MCO (4 states) providing personal protective equipment, MCO Extended Telehealth and Remote Assistance (3 states), extended pharmacy home deliveries (3 states), and MCO-provided gift cards for members to purchase groceries and other goods report (2 states).

Comments are closed.