Back to School amidst the New Normal: Ongoing Effects of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Children’s Health and Well-Being

As millions of children across the country prepare to go back to school this fall, many will face challenges due to the ongoing health, economic and social consequences of the pandemic. Children can be uniquely affected by the pandemic, having experienced this crisis at key stages in their physical, social and emotional development, and some have experienced the loss of loved ones. In addition, households with children are particularly hard hit by lost income, food and housing insecurity, and disruptions to health care, all of which have an impact on health and wellbeing. Public health measures to contain the spread of the disease have also resulted in disruptions or changes in service use, difficulties in accessing health care and increased mental health problems for children. Young children are still not eligible for a vaccination, and while children are likely to be asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, they can become infected with COVID-19. Children may face new risks due to the rapid spread of the Delta variant, and some children who become infected with COVID-19 experience long-term effects of the disease. Many of these effects have disproportionately affected low-income and colored children who faced major health and economic challenges before the pandemic. This brief report examines how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the health and well-being of children, examines recent policy responses, and looks at what the back-to-school results mean for the back-to-school season in the face of new challenges due to the recent surge in cases Deaths. The most important findings include:

- During the pandemic, some children experienced disruption to routine vaccinations or check-up appointments and access to medical care, particularly dental and specialized care. The use of telemedicine has increased, but is not enough to offset the overall decline in service use.

- Use of child mental health services has decreased due to increased symptoms of depression, anxiety and psychological stress for children and parents.

- Households with children experienced significantly higher rates of economic hardship compared to households without children throughout the pandemic, creating greater barriers to adequately addressing social determinants of health. Blacks, Hispanics and other colored people are disproportionately affected by the economic impact of the pandemic.

- Although children are less at risk of developing serious illness from COVID-19 than adults, it is estimated that over 43,000 children have lost a parent to COVID-19, with black children being disproportionately affected by parent deaths.

- Most children will likely be back in the classroom this fall, but many still face health risks due to their vaccination status or the vaccination status of their teachers. Some states and school districts are starting to post mask or vaccine requirements, while others ban vaccine or mask requirements for schools.

Recent policy developments, particularly the American Rescue Plan Act and American Families Plan, seek to alleviate some of the existing and pandemic-related problems that affect the health and well-being of children. However, there is still uncertainty about how back to school this fall will be and the transition to the “new normal” may be more difficult for some. Schools, parents and policymakers may be under additional pressure to address the ongoing effects of the pandemic on children.

Disorders in child health care and mental health challenges

The pandemic has resulted in delays in child vaccinations and preventive measures. The KFF analysis of the Household Pulse Survey from June 23 to July 5, 2021 estimates that 25% of households with children have a child who has missed, postponed, or skipped a screening appointment in the past 12 months due to the pandemic (Figure 1 ). Preliminary Medicaid administrative data confirm this pattern, showing that when comparing March 2020 – October 2020 to the same months before the pandemic in 2019, about 9% fewer vaccinations were performed for children under 2 years of age and 21% fewer child screening services were performed became. Primary and preventive care rates among Medicaid benefit recipients have shown signs of recovery in recent months, with service usage reflecting a backlog, but it is unclear whether this trend will continue and offset the millions of services that are beginning missed the pandemic. Another recent study also reports that vaccinations for all children fell sharply after March 2020. The study also finds that vaccinations recovered fully in children under 2 years of age, but only partially in older children.

Figure 1: Children missed or delayed preventive appointments and used telemedicine during the pandemic

Children also experienced access difficulties and interruptions in specialist and dental care. Parents have reported delaying dental care or having difficulty accessing dental care for their child, and there was 39% less dental care for Medicaid / CHIP recipients under the age of 19 when the March 2020 – October 2020 pandemic months with the Comparing the same months in 2019, health care needs had difficulty accessing specialized services, especially services that could not be delivered through telemedicine.

The use of telemedicine services by children has increased since the pandemic, but it is increasing has not balanced the overall decline in service utilization. Preliminary data suggests that telemedicine use for Medicaid / CHIP recipients under the age of 19 increased rapidly in April 2020 and continues to be higher than before the pandemic. 23% of households with children surveyed by the Household Pulse Survey from June 23 to July 5, 2021 stated that a child had a telemedicine appointment in the past 4 weeks (Figure 1). During the pandemic, the federal government and the federal states took measures to expand access to telehealth services. Although telemedicine use has increased, the increase has not offset the overall decline in service use, and barriers to access to health care via telemedicine may persist, especially for low-income patients or those in rural areas.

Child Psychiatry and Mental Health Service Utilization has deteriorated since the beginning of the pandemic. The pandemic caused routine disruptions and social isolation in children, which can be linked to anxiety and depression and can have implications for mental health later in life. Research has also shown that children's mental health has a negative impact when economic conditions deteriorate. Parents with young children reported in October and November 2020 that their children had increased symptoms of depression, anxiety, and mental stress, and 22% had overall deteriorated mental or emotional health. Recent studies by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that visits to the emergency room of children have increased during the pandemic for mental emergencies and suspected suicide attempts by children ages 12-17, with preliminary data for Medicaid – / CHIP benefit recipients suggest that when comparing the March 2020 to October 2020 pandemic months with the same months in 2019, there were about 34% fewer psychiatric services Access to mental health care through telemedicine has increased, but for some children still persists like face technological and privacy barriers to access to mental health services via telemedicine.

Parental stress and poor mental health due to the pandemic can have a negative impact on children's health. A previous KFF analysis found that economic insecurity has led to increased mental health problems, especially for adults in households with children and especially for mothers in those households. In addition, 46% of mothers who reported negative mental health effects from the pandemic did not have access to required mental health. Parental stress can adversely affect children's emotional and mental health, damage parent-child bonds, and have long-term behavioral effects. Maternal depression can worsen the child's health and lead to less preventive measures. In addition, parental stress and financial hardship can increase the risk of child abuse and neglect. Early evidence shows a decrease in child abuse during the pandemic, although it is unclear whether this was due to decreased reporting or social policy interventions during the pandemic. The existing and pandemic-related mental health problems of children can have an impact on the transition back to school and indicate that children may need additional mental health support when they return to school.

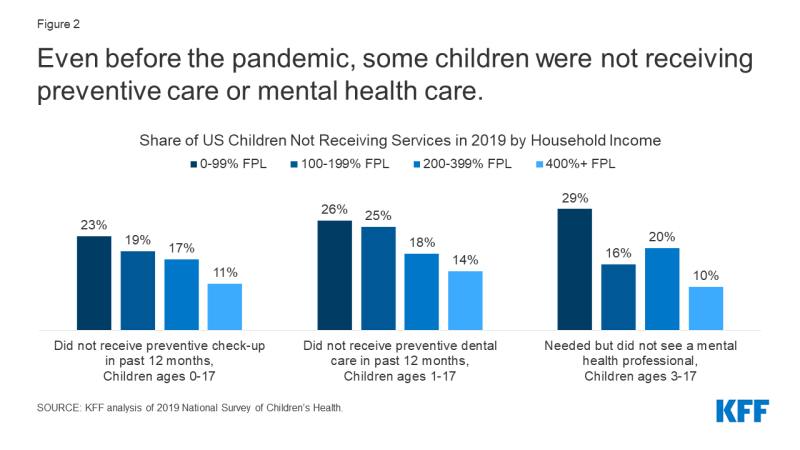

Pandemic challenges in children's access to health care that were built on a system that sometimes did not meet needs even before the pandemic, especially for low-income children. In 2019, it was estimated that 23% of children living in households with incomes below 100% of the federal poverty line (FPL) have not had a health check-up in the past 12 months, and 26% have not seen a dentist for preventive visits during the last 12 months (Figure 2). Some children with mental health needs were not cared for, with an estimated 29% of the lowest-income children in need of mental health services lacking access to medical care (Figure 2). The pandemic may have made it even more difficult for children who already have difficulty accessing health care, and likely the existing disparities in access to needed care for children of color, children with special health needs, children in low-income households and children who living in the country, areas aggravated.

Figure 2: Even before the pandemic, some children did not receive any preventive or psychological care

The economic downturn and child welfare

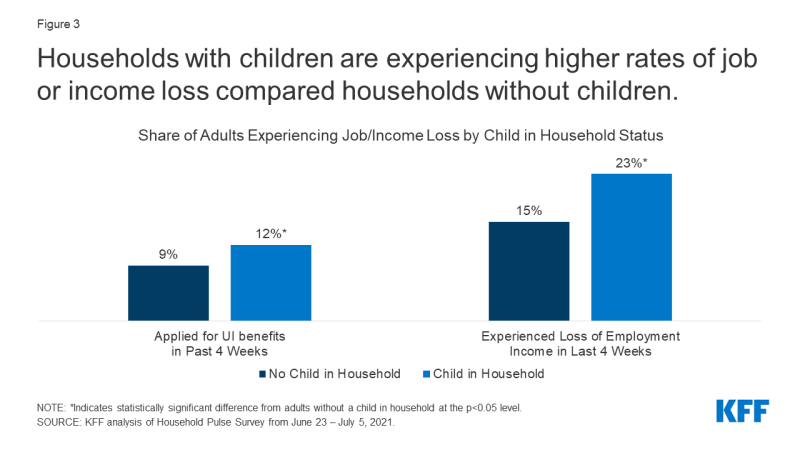

After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, many families with children faced unemployment and loss of income, and continued economic hardship. Throughout the pandemic, households with children consistently reported loss of jobs or income, with more than half of households with children reporting loss of income between March 2020 and March 2021. they are still not at pre-pandemic levels. The KFF analysis of the Census Bureau's Household Pulse Survey from June 23 to July 5, 2021 found that 12% of adults with children in the household applied for unemployment insurance (UI) benefits and 23% had lost income in the past 4 weeks (Figure 3). These rates were significantly higher compared to adults without children in the household.

Figure 3: Households with children show higher job losses or income losses compared to households without children

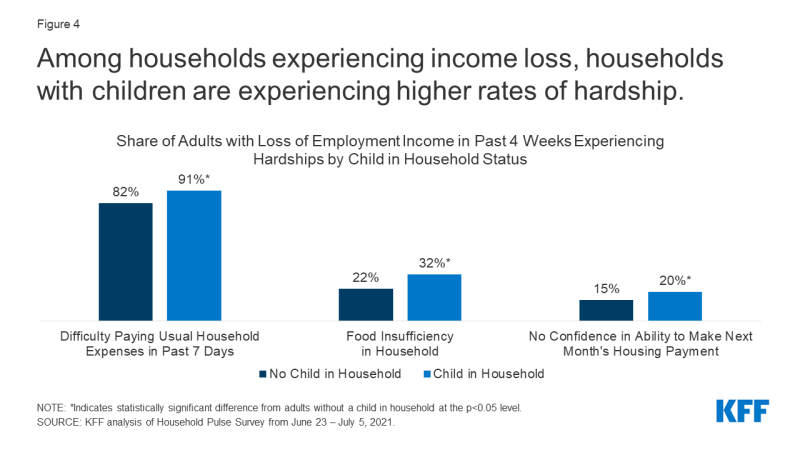

Loss of family income affects parents' ability to meet children's basic needs. The KFF analysis of the Census Bureau's Household Pulse Survey also found that 91% of adults with children in the household of adults who reported loss of income in the past 4 weeks had difficulty paying expenses in the past week; 20% said unconfident in their ability to pay the apartment for the next month and 32% reported food shortages (Figure 4). All of these rates are significantly higher for adults living in households with children than for adults living in households without children. Much research shows that economic instability is a social determinant of children's health outcomes.

Figure 4: In households with income losses, households with children are more often affected by hardship cases

Go on, black, Hispanic, and other colored households were disproportionately affected through the pandemic and its economic impact. In 2019, black and Hispanic children were almost three times more likely to live in poverty than Asian and white children, and pre-pandemic food shortages were three times higher in black households and two times higher in Hispanic households compared to white households. A recent report found that Hispanic and black households with children experienced almost twice as many economic or health difficulties as white and Asian households with children during the pandemic. Overall, the child poverty rate among children has increased during the pandemic, particularly among Hispanic and Black children.

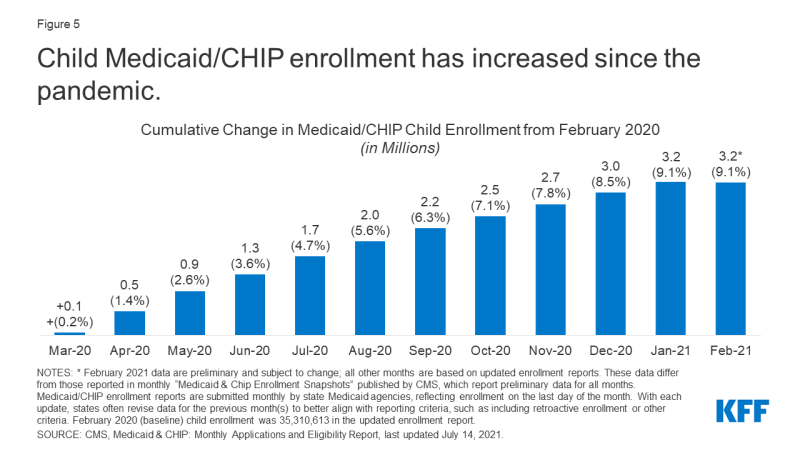

The loss of jobs and income can lead to disruptions in children's health insurance, although increased coverage from Medicaid and CHIP is likely to offset much of this decline. Approximately 2 to 3 million people lost employer health benefits between March and September 2020, a trend that builds on years of child insurance losses. From 2016 and 2019, the US uninsured child rate began to rise, although it hit the lowest rate in history (4.7%) in 2016, with the Hispanic uninsured child rate rising more than twice as fast Rate of Non-Hispanic Youth. Loss of coverage or interruptions in coverage can adversely affect children's ability to access the care they need. "During the pandemic, Medicaid and CHIP provided a safety net for many children. Administrative data for Medicaid shows that child enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP increased between February 2020 and February 2021, an increase of 3.2 million total enrollments, or 9.1% from the enrollment of children in February 2020 (Figure 5 ).

Figure 5: Since the pandemic, the number of child health aid / CHIP has increased

Child health and COVID-19

While probably Children who are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms can become infected with COVID-19. Preliminary data through July 29, 2021 shows that there have been over 4 million COVID-19 cases in children and children with underlying health conditions may be at increased risk of developing serious illnesses. Although it's a small percentage, some children who tested positive for the virus now have long-term symptoms, with Childhood Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome (MIS-C) being the most common complication affecting 4,000 children by June 2, 2021 were unclear how long symptoms persist and what impact they have on children's long-term health. The number of cases has increased in recent weeks due to the delta variant, and children make up an increasing proportion of new cases. Hospital admissions for children with COVID-19 have also increased since the beginning of July, reaching an average of 216 children who are admitted to hospital every day in the week from July 31 to August 6, 2021.

Eligible children have lower vaccination rates than the adult population, and some children are still not eligible for a vaccine. Children 12 years and older can now be vaccinated against COVID-19, which reduces the risk of adolescents contracting COVID-19, spreading, or having severe symptoms. About 37% of children ages 12-15 and 48% of children ages 16-17 received at least one dose of vaccine on July 26, 2021. These rates are lower than the adult population, which reached 70% on August 2. 2021. There is currently no COVID vaccine for children under the age of 12, so there is some risk for this population of contracting the virus and spreading it. Clinical vaccine studies for children under the age of 12 are currently ongoing and approval is expected in late 2021. The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor recently reported that nearly half of parents of children ages 12-17 report that their child has received a COVID-19 vaccine or they intend to get vaccinated right away. The report also found that parents' vaccination intentions for their children are largely correlated with their own vaccination status, and those who say their child's school provided or encouraged information about COVID-19 vaccines are more likely to report that their child is received a vaccine. The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor has also found that parents are more cautious about vaccinating their child under the age of 12. About a quarter said they would vaccinate their child between the ages of 5 and 11 as soon as the vaccine is approved, and four in 10 said they would wait and see.

Some children have experienced COVID-19 from the loss of one or more family members to the virus. One study estimates that by February 2021, 43,000 children in the US will have lost at least one parent to COVID-19. The study also finds that black children make up only 14% of children in the United States, but 20% of children who have lost a parent and low-income and colored communities had higher overall COVID-19 case rates and deaths. Losing a parent can have long-term effects on a child's health, increasing their risk of substance abuse, mental health problems, poor educational outcomes, and early death. Additionally, the death of a loved one from COVID-19 may have occurred amid increasing social isolation and economic hardship due to the pandemic. It is estimated that the number of grieving children from COVID-19 has increased by 17.5% to 20%, indicating an increased number of grieving children who may need extra support when they return to school in the fall .

Policy responses

Several guidelines passed during the pandemic have given families with children financial relief. To cope with the economic fallout from the pandemic, the federal government passed relief laws that provided direct financial relief for families, and there is evidence that material hardships that affect health, such as food shortages and financial instability, have decreased after stimulus payments. In addition, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of March 2021 provided for targeted assistance for families with children through the Child Tax Credit (CTC). The ARPA aims to reduce the number of children living in poverty by over 40%, with the expanded CTC now reaching children previously too poor to qualify and providing families in the bottom quintile with an average income increase of $ 4,470. Child poverty alleviation is linked to improved child health outcomes, such as healthier birth weight, less stress on the mother, better diet, and lower drug and alcohol use.

Other more recent directives target child health insurance or access to health care directly. To improve health insurance coverage, the ARPA has expanded the entitlement to ACA health insurance benefits for people with incomes above 400% of poverty and increased the level of support for people on lower incomes. The ARPA also provided incentives for states to expand Medicaid for low-income adults under the ACA and to extend Medicaid coverage after birth for up to 12 months, which could benefit both family health and well-being, The Child Tax Credit, extended by the ARPA, is not taxable income, so the tax credit extension does not count towards Medicaid eligibility. To address access to health care challenges, the federal government and many states are making policy changes to permanently expand access to telehealth services. In its most recent report to Congress, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) recommended more coordinated efforts by authorities to address the design and delivery of benefits and improve access to home and community-based behavioral health services for Medicaid / CHIP children with significant mental health needs. In addition, the Biden administration created a program to relieve funeral expenses related to COVID-19, but it did not include targeted services for bereaved children.

Back to school

Most children will likely be back in the classroom this fall, but many are still at health risks due to their vaccination status or teachers and the increased transmission due to the Delta variant. The vast majority of schools in the US, 88% of 4th grade schools, most of these and other schools are expected to be held in person in the fall of 2021. While many states allow in-person learning to be decided locally, nine states have required schools to return to face-to-face learning for the 2021-22 school year beginning June 2021. Currently, no states require the COVID-19 vaccine for school attendance, and some states have passed laws to ban vaccination requirements for school attendance. However, due to concerns about the Delta variant and rising cases, some counties are starting to require the COVID-19 vaccine for teachers and staff. There have been legal challenges to vaccine mandates, with a federal district court in Texas recently upheld a hospital's mandatory COVID-19 vaccination policy for employees. The CDC recently updated its guidelines on COVID-19 in schools, recommending masks for all staff and students regardless of vaccination status for fall face-to-face learning. While some states and school districts require students and staff to wear masks in school, at least nine states have passed laws banning schools from wearing masks as of late July 2021. Recent KFF polls show that a total of about half of the public have K-12. supports schools that require COVID-19 vaccination, but most parents oppose it, with divisions along partisan lines.

While returning to face-to-face learning can aid children's development and wellbeing, transitioning back to school in the fall can be challenging for some children. Experts suggest that face-to-face learning is beneficial for children's social, emotional, and physical health and can provide access to critical health services and address racial and social inequalities. However, this school year will be different for many children due to COVID-19 prevention strategies and the transition back to the "new normal" may be difficult for some, especially those who have adapted to new routines and virtual learning over the past year. Children's mental health has deteriorated during the pandemic, which could make the transition back to school difficult. Additionally, young children who were at home with their parents during the pandemic may experience separation anxiety when they switch back to school or daycare.

Schools and proposed measures can provide additional support to children and families during the transition to school. The increased child tax credits started July 15 and continue monthly, but the expanded CTC wasn't passed until 2021. The American Families Plan put forward by the White House proposes extending the CTC expansion through 2025 and crediting families with no earnings. The American Families Plan also suggests expanding school meals and access to healthy foods, making the summer EBT program permanent, and expanding SNAP eligibility for previously incarcerated people. The American Families Plan also proposes a national paid family and sick leave program, as well as a universal pre-kindergarten, which research has shown to be beneficial for child health with tax credits and investments in general preschool, childcare, paid vacation, and education. Other policies at the local level can also address children's well-being. For example, schools and school districts can support students re-entering school by creating a safe personal learning environment, providing staff and resources to support students with transition problems, ensuring that staff and teachers have access to mental health resources and develop a trauma-informed plan to respond to COVID-19-related trauma.

COVID-19 and the healthcare disruptions, mental health issues, and economic hardships caused by COVID-19 all impact children's health and their transition back to school in the fall. While returning to face-to-face learning can aid children's development and wellbeing, uncertainty remains about what face-to-face learning will look like as delta cases are increasing and the transition to the "new normal" can be difficult for some children could and their families. Recent policy developments seek to address the ongoing effects of the pandemic on children, and schools, parents and policy makers may face additional pressures to support children during this time.

Comments are closed.