Challenges in the U.S. Territories: COVID-19 and the Medicaid Financing Cliff

More than a year after the public health emergency, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect the lives of Americans, including those who live in the U.S. Territories. Prior to the pandemic, the U.S. territories – American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) – faced a number of long-standing tax and health challenges, exacerbated by recent Natural disasters. Differences in Medicaid funding, including a legal cap and match rate, have contributed to broader challenges for the financial and health systems in the areas. While additional federal funds have been made available above the statutory ceilings, these funds are expected to expire at the end of September 2021. Without additional action by Congress, the territories will lose the vast majority of Medicaid funding, which could result in a reduction in coverage, services and benefits. and provider rates that could adversely affect the areas when addressing the long-term health and economic consequences of the pandemic. This letter examines how the pandemic is affecting the areas and the issues surrounding Medicaid's impending fiscal cliff.

Health status and systems in pre-pandemic areas

Even before the pandemic, residents of the U.S. territories had a number of health differences compared to the states. For example, Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands (USVI) have higher overall diabetes rates compared to the United States, while Puerto Rico also has higher overall infant mortality rates compared to the United States. American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), and Guam all have higher rates of obesity, high blood pressure, and smoking compared to the United States.

In addition, the health systems in the US territories are facing long-term challenges, including delayed repairs to hospital facilities and serious provider shortage issues. Recruiting and retention are difficult because the salaries for vendors in the territories are much lower than for vendors in the US, although vendors in most territories must be US licensed. Carrier limitations and system capacity sometimes require patients to be cared for off-island. For example, before building its own oncology center on the island, CNMI sent over 300 patients a year to Guam or Hawaii for treatment.

These health system challenges have been greatly exacerbated by recent natural disasters that happened before the pandemic. Typhoons, earthquakes, mudslides, and volcanic eruptions across the areas have severely damaged hospital facilities, increased provider drain, and increased the total number of patients as well as the number of patients with more complex mental and physical health needs.

Impact of the introduction of COVID-19 and vaccines in the areas

At the start of the pandemic, the U.S. Territories faced COVID-19 testing restrictions, which is why COVID-19 cases and deaths may not be adequately reported. As of March 2020, only Guam and Puerto Rico were able to conduct COVID-19 tests in their public laboratories, but faced limited capacity due to material and staff. The other three areas had to send their test samples to Hawaii or the mainland, which resulted in a longer turnaround time for the results until they purchased their own test and analysis equipment. While Puerto Rico had public labs to run testing, it had the lowest per capita testing rates of any state in the spring of 2020 and struggled to get the supplies it needed to increase its testing capacity. Guam, on the other hand, lacked staff to carry out tests.

The pandemic exposed pre-pandemic health system problems that persisted after the natural disasters. With the rise in COVID-19 cases, most areas were quickly reaching hospital and ventilator capacity and had to recruit healthcare providers, especially nurses, from mainland America or neighboring international islands. “For example, in September 2020 in Guam as the death toll increased and as more vendors left the island, island officials searched for 100 nurses from mainland USA or the nearby Philippines. An infusion of funds from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) helped some hospitals purchase additional hospital equipment and personal protective equipment (PPE).

In Puerto Rico, the average daily number of cases increased in March and April, while the other areas remained stable. American Samoa is the only U.S. territory that has not had any cases or deaths to date. Despite the March and April surge in Puerto Rico, recent data shows a significant decrease in the average daily case numbers. On May 12, 2021, the average daily case per million in Puerto Rico was 90.6 compared to 38.4 per million in Guam and 5.0 per million in CNMI. The average daily cases per million in USVI increased in early May, and as of May 12, it is the only current area to surpass the US rate of 111.9 cases per million (USVI had 139.3 cases per million population) .

Due to the previous surge in cases, Puerto Rico has taken stricter precautions. Early on, Puerto Rico issued overnight curfews and lockdown orders punishable by fines or imprisonment. Shops were fully reopened in June 2020, but the curfew remained. Personal schooling reopened in March but closed as cases increased in April and from April 28th. Travelers must provide evidence of a negative COVID-19 test or face a $ 300 fine.

Similar to the states, CNMI, Guam and USVI have also imposed bans, including some travel restrictions on the islands, but are slowly reopening stores with varying levels of capacity and service. USVI has so far not changed its reopening plans to address the recent surge in cases in early May. American Samoa, which has not reported any COVID-19 deaths, had introduced social distancing and school closings back in December 2019 due to a measles outbreak. In response to the pandemic, the government stopped all flights inside and outside the island in March 2020, allowing only one weekly cargo flight for medical and food supplies. All American Samoa residents who left the island during the pandemic were not allowed to return until early 2021.

The proportion of people aged 16 and over who were fully vaccinated more than doubled between March 1 and May 1, 2021, and quadrupled in some areas (Figure 1). By May 1, every area except Puerto Rico and USVI had fully vaccinated more than 30% of the eligible population. The areas have received vaccines at rates similar to the US states. However, some areas administer a lower proportion of the vaccines supplied compared to the US as a whole. As of May 12, 2021, the proportion of delivered doses administered in the US was 78.5%, while the proportions of CNMI and Puerto Rico were significantly lower (at 60.3% and 63.1% of administered delivered doses, respectively). Problems with vaccine administration can be caused by staff shortages, problems reaching residents in more remote areas, or delay in reporting.

The US territories followed a similar vaccination approval protocol as the US, with priority given to the elderly, healthcare workers, and other key workers. In addition, all U.S. territories opened COVID-19 vaccinations for all adult residents before President Biden's April 19 deadline. In addition, the areas used vaccination approaches tailored to their island's needs in order to reach a higher proportion of their population. For example, CNMI has strategically addressed the elders in the community, while American Samoa, which has only one public hospital, used a drive-through vaccination center as an additional means to reach a higher percentage of its population.

Figure 1: The proportion of people aged 16 and over who have been fully vaccinated has more than doubled in the U.S. Territories since March 2021.

Important funding issues for the areas

Before the pandemic, most areas faced tax burdens that were exacerbated by natural disasters or emergencies. For example, USVI experienced over 30% economic downturns between 2008 and 2016, accompanied by population and job losses in certain industries, while Puerto Rico experienced years of economic recessions and debt that ultimately led to the creation of the Financial Oversight and Management Board (FOMB). These economic challenges were exacerbated by the natural disasters, which accelerated the brain drain, destroyed homes, schools, businesses and other infrastructures, and resulted in lost revenue with reduced tourism and economic activity.

The structure of Medicaid funding for the areas has also added to the financial burden. Unlike the 50 states and DC, Medicaid's annual federal funding in the US Territories is subject to a statutory cap and a fixed matching rate. In contrast to the state legal formula, which is unlimited and adjusted annually based on a state's relative per capita income, the area's federal matching rate (known as the federal FMAP (Federal Medical Assistance Percentage)) is determined by law. The US Territories FMAP rate is set at 55% (although it has increased after natural disasters and public health emergencies). However, if the matching rates were calculated using relative per capita income, all territories would receive a higher FMAP, likely at or near the maximum allowable match rate of 83%. Notwithstanding temporary aid, once an area has used up its limited federal funds, it will no longer receive financial aid for its Medicaid program for that fiscal year. This puts additional pressure on the territory's resources if Medicaid spending continues beyond the federal ceiling. This means that the effective matching rate is lower than the statutory rate.

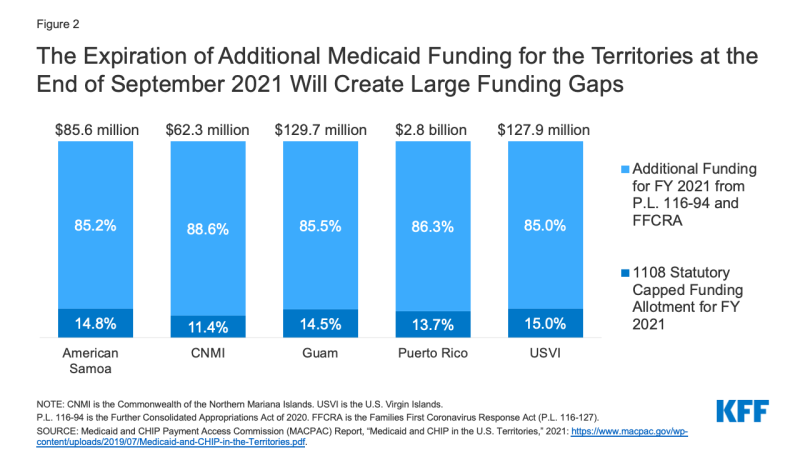

Over time, Congress has increased federal funding for the areas in general and in response to specific emergencies. Temporary funding can bring short-term relief, but it can also create cliffs for financial funding that require ongoing action by Congress. The allocations for each of the areas for Fiscal Year 2020 and Fiscal Year 2021 are approximately seven to nine times the legal level, as additional funding has been added from the Funding Package for Fiscal Year 2020 and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) (Figure 2 ). Puerto Rico was entitled to an additional $ 200 million in fiscal 2020 and 2021, subject to a provider rate increase of at least 70 percent of the cost Medicare Part B would pay for services. In addition to increasing federal funding, traditional territory was increased from 55 percent for Puerto Rico to 76 percent by fiscal 2021 and 83 percent for the territories (with an additional 6.2 percentage point increase as part of the Medicaid tax relief that applies to all states and state areas are available if certain conditions for maintaining eligibility are met). Recent congressional statements suggest that additional federal funding has been used in Puerto Rico to support increased coverage, additional benefits (such as treatment for hepatitis C) and higher reimbursement for hospitals, doctors and managed care plans.

While limited federal funding is often a limitation on territories, territories have occasionally had difficulty raising their share of the funding required to draw federal funds. Loss of local revenue, particularly tourism revenue, from both past natural disasters and COVID-19, can affect the areas' ability to use their federal funds. Increasing the federal match rate would help the territories by requiring less territorial funding to gain access to additional federal funding.

If Congress doesn't act, the U.S. Territories will lose over 80% of their funding and there will be a major Medicaid funding cliff by the end of fiscal 2021. Without federal action, the territories would have to make significant changes to their programs to lower Medicaid providers' payment rates, benefits, or eligibility criteria while managing the effects of the pandemic.

Figure 2: The expiration of additional Medicaid funding for the territories in late September 2021 results in large funding gaps.

What To See When Looking To The Future

New federal funding and vaccine delivery efforts will help fight the pandemic. The American Rescue Plan Act provided payments of $ 4.5 billion to the Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund to respond to the "negative economic impact of COVID-19," and $ 700 million for critical capital projects to "enable labor, education and health monitoring directly in response to COVID-19," which may help alleviate some economic challenges for the islands.

The expiration of Medicaid's temporary funding in late September 2021 will create a huge tax cliff if Congress fails to act. The Territories could lose most of Medicaid's federal funding as the temporary funding represents more than eight out of ten Federal Medicaid dollars in each Territory. Without federal action, the territories would have to make significant changes to their programs to lower Medicaid providers' payment rates, benefits, or eligibility criteria while managing the effects of the pandemic.

Congress might consider increasing the caps or more fundamental changes to Medicaid funding, such as: B. the lifting of the funding ceiling and a review of the definition of the FMAP. An increase in the funding ceilings could help in the short term. Congress may also make proposals to lift Medicaid funding limits in areas such as the Insular Area Medicaid Parity Act (HR 265), the Territorial Equity Act of 2021, or proposals to move funding from the current structure to parity with other government programs consider over time (such as HR 3371 from last Congress that would achieve Medicaid funding for Puerto Rico over 10 years). A temporary increase in spending caps in the areas could avert the impending fiscal cliff. However, such a measure could lead to another fiscal cliff in the future and lead to uncertainties about the availability of federal funds in the longer term, without any permanent change in funding.

Comments are closed.