COVID-19 Vaccination among American Indian and Alaska Native People

Summary

With the spread of the COVID-19 vaccine, ensuring equitable and timely distribution to the US population will be important to mitigating the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on people of color, preventing future racial health disparities, and widespread immunity among the population to reach. Because of the underlying inequalities, the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected American Indians and Alaskans (AIAN), who account for more than 5 million people in the United States. At the same time, vaccination rates among AIAN people have so far been above average. This letter presents available data on COVID-19 vaccinations in AIAN individuals from federal and state sources and discusses factors that contribute to the success of these vaccination efforts. It finds:

The underlying inequalities that existed prior to the pandemic are contributing to the fact that AIAN people are increasingly faced with barriers to accessing health care and disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The chronic underfunding of the Indian Health Service (IHS) relative to health needs and the high uninsured rates add to the barriers to health care for the AIAN population. Existing social, economic and health inequalities have also resulted in higher disease and death rates among AIAN people due to COVID-19.

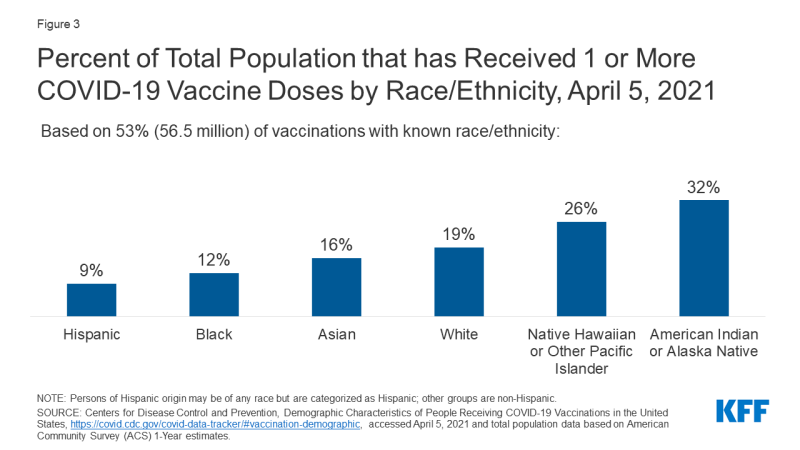

Data available so far show that AIAN people are more likely to be vaccinated compared to other racial / ethnic groups. Federal data shows that 32% of AIAN people received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine compared to 19% of whites, 16% of Asians, 12% of blacks, and 9% of Hispanic Americans as of April 5, 2021 Government data similarly show higher vaccination rates in AIAN individuals compared to other groups.

The high vaccination rate among AIAN individuals largely reflects the leadership of the tribes in implementing strategies to prioritize and distribute vaccines that meet the preferences and needs of their communities. The high rates may also partly reflect the larger supply of vaccination doses being dispensed to the IHS compared to the number of people cared for compared to government vaccination programs. Tribes have supported and built upon existing trusted community resources and providers in the distribution of vaccines. The successes that tribes have had in vaccinating their communities provides lessons that can help improve future vaccination efforts.

Background: Health and health care for AIAN people

According to treaties and laws, the federal government has a unique responsibility for providing health services to AIAN individuals. The IHS is the primary tool the federal government uses to exercise this responsibility for members of nationally recognized tribes who make up approximately 2.6 million of the 5 million or more people who identify as AIAN nationwide. The IHS offers services directly through Tribal-powered health programs and through services purchased from private providers. The IHS also funds urban Indian organizations to make health services available to people who live in urban areas that make up most of the AIAN population.

Due to long-term restrictions and underfunding of the IHS, AIAN employees face disproportionate barriers to accessing health care. IHS services are generally limited to members or descendants of members of nationally recognized tribes, and not all individuals who identify themselves as AIAN belong to any of these tribes. IHS has historically been underfunded to meet the health needs of AIAN employees and access to services through IHS often varies by location. Given the limitations of IHS, Medicaid and other health insurance sources remain important in expanding access to care for AIAN individuals. However, as of 2019, 22% of the not older AIAN people were uninsured, the highest of all racial and ethnic groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Uninsured rates in the non-elderly population by race / ethnicity, 2019

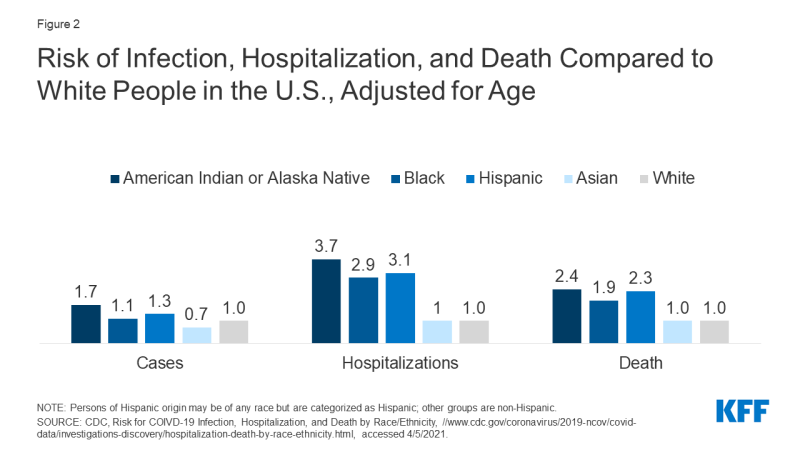

The COVID-19 pandemic hit AIAN people disproportionately. AIAN people are at increased risk of exposure to the virus due to social and economic factors and have a higher rate of health conditions that put them at increased risk of serious illness when contracted with coronavirus. Because of these increased risks, AIAN people are almost twice as likely to be infected with the virus, almost four times as likely to be hospitalized, and almost two and a half times more likely to be diagnosed with COVID due to age. 19 die like their white counterparts – adjusted data (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Risk of infection, hospitalization, and death versus white people in the United States, age-adjusted

COVID-19 vaccination among AIAN people

The federal government issues COVID-19 vaccines directly to the IHS, and tribal health programs and urban Indian organizations decide whether to get vaccines directly from the IHS or through their respective state distribution mechanisms. By March 15, 2021, 351 of the 609 IHS facilities, tribal health programs, and Urban Indian Organization facilities had chosen to receive vaccines directly through IHS. Institutions can change their choices. When tribal health programs and urban Indian organizations elect to obtain vaccines through the state, the CDC offers the state "Sovereign Nation Supplementation of Vaccine Doses." CDC data shows that by April 5, 2021, nearly 1.5 million doses of vaccine had been delivered to IHS, over 1 million doses were given through IHS, and more than 630,000 people had received at least one dose through IHS, which is over 30% of that Population served by IHS.

Data available so far suggest that AIAN people are more likely to be vaccinated compared to other racial / ethnic groups. Data gaps limit the ability to get a complete picture of who is being vaccinated and how vaccination rates differ between groups. However, data available so far show that AIAN people are more likely to be vaccinated compared to other racial / ethnic groups. For example, federal data from CDC, which was available for about half of those who received at least one dose as of April 5, 2021, suggests that over 720,000 AIAN people received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose, which is more than makes up 30 percent of the 2.2 million people who identify themselves exclusively as AIAN (Figure 3). In contrast, these data show that 19% of whites, 16% of Asians, 12% of blacks, and 9% of Hispanic Americans had received at least one dose of vaccine.

Figure 3: Percentage of the total population who received one or more COVID-19 vaccine doses by race / ethnicity, April 5, 2021

State-level data on vaccinations for AIAN individuals are limited. As of March 29, 2021, only 36 states reported vaccinations among AIAN people. In addition, the data reported by the state does not reflect vaccines administered through referrals through IHS, and therefore may underestimate vaccination rates and further limit the ability to calculate reliable estimates. However, data from several states show that AIAN people are more likely to be vaccinated compared to other groups. For example, in Alaska, 22% of vaccinations went to AIAN people while they make up 15% of the population. The pattern is similar at the circle level. On April 5, 2021, districts with a high percentage of AIAN people had a higher average vaccination rate (20%) compared to the average of all districts and districts with a low percentage of AIAN people (19% and 18%, respectively).

Factors Contributing to High AIAN Vaccination Rates

The high vaccination rate among AIAN people is in stark contrast to the previously observed gaps in vaccination for blacks and Hispanic Americans. The underlying inequalities and barriers to health care for the AIAN population could also have created barriers to vaccination. However, experience suggests that the autonomy given to tribes in designing and implementing vaccine distribution efforts between their communities has contributed to the success of vaccinating the population. The high rates may also partly reflect the greater supply of vaccination doses being dispensed at the IHS compared to the population supplied compared to government vaccination programs. As of April 5, 2021, more than 1.5 million doses had been delivered to IHS, which is roughly 75,000 per 100,000 people served by IHS. Only 2 states and Washington DC were given higher dosage rates than the IHS, although the IHS dosage rate is lower compared to these states. Additionally, the availability of more complete race / ethnicity data for AIAN people receiving the vaccine, as many receive it through IHS, Tribal Health, and Urban Indian Organization facilities, may also contribute to the high rates. Federal and some state data show high proportions of vaccinations of unknown or “different” race / ethnicity, which can affect vaccination rates between races / ethnic groups.

IHS, tribal health programs, and urban Indian organizations have the autonomy and flexibility to implement priority and distribution strategies that suit the needs and preferences of their communities. The IHS developed a COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force (VTF) to advance plans for prioritization strategies, vaccine administration, distribution, data management, security and monitoring, and communications. In accordance with the recommendations of the Federation of the Advisory Committee on Vaccination Policy (ACIP), IHS initially prioritized health care workers and residents of long-term care facilities. The IHS assigned starting doses were estimated to be sufficient for 100% of healthcare workers and residents of long-term care facilities. Like states, tribes and urban Indian organizations have the power to make their own prioritization decisions. Many chose to prioritize elders, and some, like the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, prioritized native speakers to protect themselves from further loss of culture and tradition threatened by the pandemic. Several tribes, including the Chickasaw Nation, Cherokee Nation, and Lummi Nation, have had so much success in vaccinating their priority groups that they have expanded the spread to non-native members of the public.

Tribes build on existing trusted community resources and vendors and assist them in distributing vaccines. Tribes leverage the networks and resources in the community and leverage years of experience to reach tribal members with various access barriers. For example, the Navajo Nation has vaccinated between 4,000 and 5,000 homebound citizens by working with public health workers to reach out to these residents in rural communities. In Alaska, tribal health organizations relied on longstanding strategies designed to reach geographically isolated communities, including partnering with local pilots to transport pharmacists and vaccine bottles to such areas. In addition, many tribes have set up vaccination system registration systems to suit the resources and preferences of their populations. For example, media reports pointed out that many tribes have set up call centers to answer inquiries, book appointments, and reach people.

Tribes have tailored contact and communication plans in place that share culturally relevant messages through trusted people in the community. A national survey of AIAN people conducted in late 2020 found that the majority were willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine and that the most common motivations for a vaccine were a sense of responsibility to protect the local community and preserve cultural pathways. Regardless of willingness to receive a vaccine, the most commonly reported concern about the vaccine was how quickly the vaccine was moving through clinical trials. Some tribes have used fluent language speakers to address concerns about the vaccine in the community. For example, the Cherokee Nation prioritized the Cherokee language speakers to generate optimism and show that the vaccine was safe. Similarly, the Navajo Nation employed fluent doctors and health professionals to serve as a trusted source of information about the vaccine.

looking ahead

Given the varying effects of COVID-19 on the AIAN population and the barriers and challenges to accessing health care, it is particularly important to ensure access to the COVID-19 vaccine. Data available to date shows high COVID-19 vaccination rates among AIAN individuals, largely reflecting the role of the tribes in developing and implementing strategies to distribute vaccines that meet the needs and preferences of the communities they serve. The successes that tribes have had in vaccinating their communities provides lessons that can help improve future vaccination efforts. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides IHS with an additional $ 600 million for vaccination efforts, $ 1.5 billion to track COVID-19 infections, and $ 240 million to set up and maintain a COVID 19 public health workforce and $ 600 million for COVID-19-related facilities improvements that may further enhance the tribes' vaccination efforts and their response to COVID-19.

Comments are closed.