Kids’s Well being and Effectively Being Through the Coronavirus Pandemic

Summary

The debate over school openings has highlighted the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on children and their families. While experts continue to collect data on children's risk of contracting and transmitting the coronavirus, recent research suggests that while children are more asymptomatic and less likely to suffer from serious illnesses than adults, they can spread it to other children as well as adults . In addition to the risk of disease, COVID-19 has resulted in changes in schooling, health service delivery, and other disruptions to normal routine that are likely to affect the health and well-being of children, regardless of whether they are infected.

This brief report examines how a range of economic and societal disruptions due to COVID-19 can affect the health and well-being of children and families. It draws on published literature, as well as pre-pandemic data from the National Child Health Survey and National Census for School-Based Healthcare, up-to-date survey data on experiences during the pandemic, data tracking the number of cases resulting from school openings , and preliminary reports based on damage data to assess service use among Medicaid and CHIP child recipients. It is found that school openings / closings, social distancing, loss of health insurance, and disruptions in medical care can negatively impact the health and well-being of children in the United States (Figure 1). The main results include:

- Students who attend a school in person are at direct risk of contracting coronavirus. With early follow-up, nearly 12,400 cases in 3,900 schools are documented. Schooling risks may be higher for low-income or skin-colored children whose families may be less able to afford alternative school arrangements or private transportation to school. A KFF poll in July found that skin-colored parents were significantly more likely than white parents to say they are concerned that their child is getting sick with coronavirus from attending school and that their school did not have sufficient resources to reopen safely.

- Students who do not attend school in person are also exposed to health risks, including difficulty accessing health services normally provided by school, social isolation, and reduced physical activity. Millions of children have access to health services through school-based health clinics, school screening and early intervention programs, and on-site counseling. These services can be suspended in schools that are not open for personal instruction. Children may also lack opportunities for social contact or exercise, as three-quarters of school-age children participate in a sport, club, or other organized activity or lesson, many of which may be exposed. A quarter of children do not live in a neighborhood with access to sidewalks or sidewalks, which could limit physical activity. KFF surveys show that parents often (67%) have concerns about their children's social and emotional health due to school closings.

- Both students in and out of personal schooling may experience emotional or behavioral disorders resulting from routine disruptions as well as increased parenting stress and family difficulties. Early research has documented high rates of attachment, distraction, irritability, and anxiety in children, especially younger children, as well as increases in substance use among adolescents, and a survey found that nearly a third of parents said their child had experienced harm for their emotional or mental health. Parental stress from childcare, schooling, loss of income, or other pandemic stresses can adversely affect children's emotional and mental health, affect parent-child bonding, have long-term behavioral effects, and have serious or neglectable effects on vulnerable children. Exposure to adverse childhood experiences has documented the effects of lifelong physical and mental health problems.

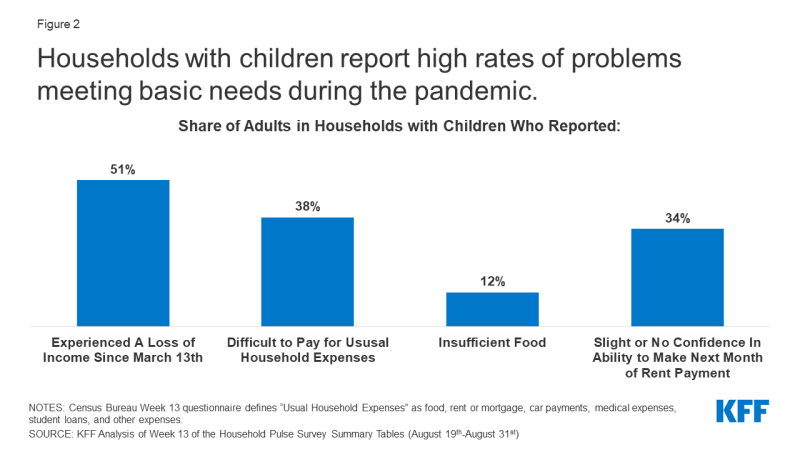

- Children are also suffering from the aftermath of the economic impact of the pandemic. At least 20 million children live in households where someone has lost a job. Although the vast majority of children who lose access to employer-sponsored insurance due to job loss are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, some parents may have children due to difficulty completing the application, lack of knowledge or understanding of eligibility or do not include reasons for this in the insurance cover for other reasons. Many families with lost incomes, food shortages or rent problems since the pandemic have children, and school closings can make access to these meals difficult for the 20 million students who receive free or discounted lunches.

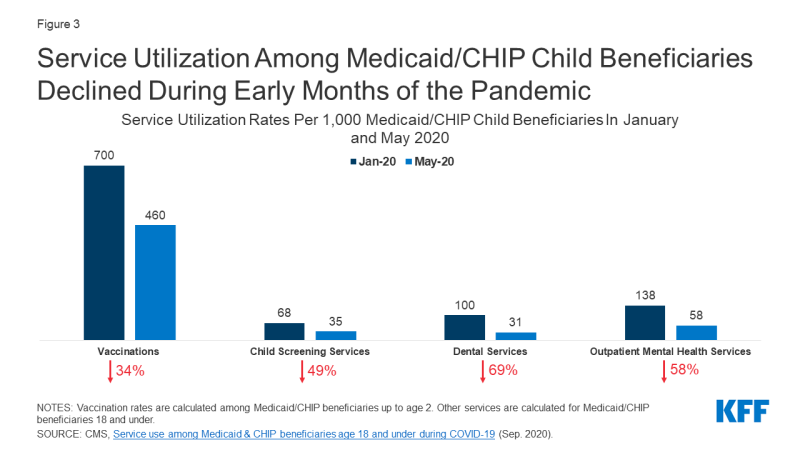

- Parents may delay preventive and ongoing care for their children due to social distancing measures and exposure concerns. Reports based on health claims show decreases in vaccination rates, child screenings, dental services, and outpatient psychiatric services among Medicaid / CHIP child recipients (Figure 3). Other administrative data shows declines in the ordering and administration of vaccines, particularly among children older than 24 months. It is likely that parents are delaying care because of illness or cost issues, and that providers may have limited capacity due to changes in operations to safely treat patients. These delays in care can disproportionately affect the 13 million children with special health needs who require ongoing care to meet their complex needs.

Children's lower risk of serious illnesses due to COVID-19 has led most of the pandemic discussions and policy debates to focus on high-risk adults, although the recent debate on school openings put an emphasis on the health and wellbeing of Children. Many children currently face significant barriers to entry, emotional distress, and financial difficulties that could have long-term effects on their lives. Measures to ensure access to the health services they need, particularly behavioral health services, as well as facilitating access to social services in support of families with children can help address some of the consequences children currently face.

Figure 1: Factors that negatively impact the health and wellbeing of children during COVID-19

introduction

The school opening debate has highlighted the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the country's 76 million children and their families. Experts continue to collect data on children's risk of contracting and transmitting coronavirus. However, recent research suggests that while children are more asymptomatic and have fewer serious illnesses than adults, they can be transmitted to both children and adults. According to state data, there were more than half a million COVID-19 cases in children nationwide as of September 17, 2020, which is just over 10% of all cases (children make up about a quarter of the population in the US). However, new cases in children between September 3 and September 17 represented a 15% increase over the period two weeks earlier. In addition, social distancing measures and the economic downturn have important implications for the health and well-being of children, especially low-income children and children of skin color. These groups faced heightened health, social and economic challenges prior to the pandemic. Research shows that minority and socio-economically disadvantaged children, like adults, have a higher risk of contracting coronavirus. This report provides an analysis of the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's mental and physical health, wellbeing, and access to and use of health services.

Health risks due to school openings / closings and social distancing policies

States and school districts have made different decisions about how school will run in the 2020-21 school year. As of Sept. 23, only Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia had statewide school closings, with five other states having regional mandatory closings, while four states ordered that face-to-face tuition be available full-time or part-time. The rest of the states have either left school operations decisions to the local community or are using a hybrid (personal and online) approach to school openings. Most states have given childcare facilities that serve younger children through Pre-K the option to open, sometimes with class size restrictions or other surgeries.

Students who attend school in person are at direct risk of contracting coronavirus early on persecution Documentation of almost 12,400 cases in 3,900 schools. A KFF review revealed this evidence It is inconsistent whether children are less likely to become infected than adults when exposed, and while the severity of the disease is significantly less in children, a small subgroup becomes quite ill. It was also found that while school openings in many other countries did not result in student outbreaks, the US has a much higher community transmission rate, lower testing and contact tracking capabilities and may perform differently. In addition, experiences from other countries and daycare centers in the United States show that school-related outbreaks occur and children transmit the virus. The KFF survey data from July 2020 showed a high level of concern among parents about health risks due to the reopening of the school. 70% of parents of a child aged 5 to 17 said they were somewhat or very concerned about their child getting sick due to coronavirus attending school; Colored parents were more likely to express this concern (91% versus 55% of white parents) and were also more likely to say that their child's school does not have the resources to reopen safely (82% versus 54% of white parents). As of September 22, the National Education Association has confirmed nearly 12,400 cases in Pre-K to high school students across the country. Given the lack of universal tests among students in school and the greater likelihood that children are asymptomatic, the number of cases is likely higher than advertised. Children infected with coronavirus can also pose a risk outside of their school community, as 3.3 million adults aged 65 and over live in a household with a school-age child.

The risk of developing coronavirus from school may be greater for low-income or minority students due to different school structures and commuting patterns. Risks due to school and parents' decisions about the school year have exposed and exacerbated inequalities in the education system. Children in low-income families are less likely to have access to a "learning pod" to support in-home teaching, and are less likely to have adequate computer resources at home for distance learning, and therefore may be less likely that they unsubscribe from in-home lessons. In addition to being at greater risk from face-to-face presence, minority or low-income children may be at greater risk when traveling to and from school because low-income students may lack alternatives to school transport or live in residential areas with no safe walking paths to school. Data from the 2017 National Household Travel Survey shows that a higher proportion of low-income students drive a school bus than non-low-income students (60% versus 45%). In addition, black students travel further to school than white and Spanish students. Longer commutes on school buses and other public transport can increase the risk of contracting the virus as more time is spent in a closed and crowded space.

Students who do not attend school in person may have difficulty accessing health services that are normally provided through the school. School-Based Health Clinics (SBHCs) provide primary care and behavioral medicine to nearly 6.3 million students in over 10,600 public schools in the US, accounting for nearly 13% of students across the country. These clinics are mainly located in schools that serve a high concentration of low-income students, and mostly students from 6th grade and up. In addition, only a small fraction (just over 10%) of SBHCs are telehealth clinics, while the remainder provide all or most of the services in person. While some SBHCs may stay open as they serve the wider community and close schools, many other SBHCs have likely closed as well, removing a source of care for students who rely on them. Outside of SBHCs, schools also offer their students checkups, early interventions, and other health services. In 2016-2018, nearly 1 in 4 students aged 5-17 had their eyesight tested in school (23%), and nearly 10% of children aged 3-17 with Autism Spectrum Disorder had their first time Diagnosis made by school psychologist or counselor. Approximately 200,000 students in the United States between the ages of 10 and 17 reported using the nurse's or exercise coach's office as a common source of care. Prior to the pandemic, 58% of adolescents using psychiatric services received those services in an educational setting with higher rates among low-income minority students.

Social distancing measures can lead to a decrease in children's social connections and physical activity. Over three-quarters of older children between 6 and 17 years of age participate in sports after school or at the weekend, are members of a club or organization after school or at the weekend, or take part in some other form of organized activities or lessons, e.g. music, Dance, language or other arts. Many of these activities are likely canceled or restricted due to social distancing measures (even when schools are open), leaving many children with no social or physical involvement. Parents report great concern about limited social interaction. Data from a July KFF survey found that 67% of parents fear their children will fall behind socially and emotionally if schools don't reopen. As recreational facilities remain closed, exercise or outdoor opportunities may be limited. Over 1 in 4 families do not live in a neighborhood with sidewalks or sidewalks, which could limit children's ability to spend time outdoors and maintain good health.

Both students in and out of personal schooling may experience emotional or behavioral disorders due to interruptions in routine. There have been widespread reports of the challenges that pandemic disorders and stress pose to the mental health or behavior of children. Early research reported high rates of attachment, distraction, irritability, and anxiety in children, with younger children more likely to exhibit these behaviors. In a June 2020 survey, 29% of parents said that their child had already suffered damage to their emotional or mental health. Children with pre-existing mental or behavioral health problems can be at particularly high risk. Before the pandemic, more than one in ten teenagers between the ages of 12 and 17 had depression or anxiety. The prepandemic rates of mental illness were higher in children of color, and they were also less likely to receive treatment for their mental or emotional problems. Substance use is also a problem, and research has shown that single substance use among adolescents increases during the pandemic, which is linked to poorer mental health and coping. Behavioral medicine treatments include frequent contact with therapists and regular follow-up visits, which can be affected by limited access to services or school closings during the pandemic. Research has documented long-term effects of negative childhood experiences, including lifelong physical and mental health problems.

An increase in parental stress can also adversely affect children's health. Due to the long-term closure of schools and daycare centers, many parents face new challenges in childcare, homeschooling and disrupting normal routines. Prior to the pandemic, more than half (52%) of all children ages 0-5 received at least 10 hours of care per week from someone other than their parent or guardian, including daycare, preschool or head start programs. During the pandemic, almost all adults in households with children at school reported disruption to normal schooling. With many sources of care unavailable, parents who are still working (either face-to-face or teleworking) need to balance childcare or schooling with work. KFF tracking surveys, conducted after widespread shelters, found that more than half of women and just under half of men with children under 18 reported negative effects on their mental health due to coronavirus worry and stress . Parental stress in dealing with the pandemic can adversely affect children's emotional and mental health, affect parent-child bonding, have long-term effects on behavior, and have serious effects on children who are at risk of abuse or There is neglect. A survey conducted at the end of March 2020 found that a majority of parents (61%) had yelled, yelled at or yelled at their children at least once in the past 2 weeks and 20% had beaten or hit their child at least once in the past 2 weeks. Social distancing can result in children having less access to support systems outside of the household.

Health risks from loss of family income

COVID-19 has increased unemployment and decreased income for many families with children. The social distancing measures required to cope with the crisis have led many companies to cut working hours, cease operations, or close entirely. KFF estimates of job losses between March 1 and May 2, 2020, there are over 20 million children in a family where someone lost a job. The loss of jobs has continued since that date and a greater number of children may be in a family where someone has kept their job but has suffered some loss of income. Data from the Census Bureau's Household Impulse Survey shows that as of August 31, just over half of adults who have children in the household have had some loss of income from work since March 13, 2020, a higher rate than adults without children ( 42%). and over 30% of adults with children expected a loss of income in the next four weeks (Figure 2).

Job loss can disrupt children's health insurance, although most children in families who lose employer-sponsored health insurance are likely to be eligible for coverage under the ACA. KFF's analysis of job losses and potential loss of employer coverage from early May found that millions of people who lost their jobs on May 2 were at risk of losing their employer health benefits, and over 6 million people had the risk of losing and becoming ESI Children are not insured. The vast majority of these children are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP coverage, but it is unclear whether they will be eligible for coverage. Between 2016 and 2018, more than a third of families who had a coverage gap attributed the gap to unaffordable insurance, termination of health insurance due to overdue premiums, or a change in employer or employment status. Loss of coverage among children negatively affects their ability to access the care they need. ,,,

The loss of family income also affects the parents' ability to meet the children's basic needs. Data from the Household Impulse Survey from August 19 to 31 shows that 38% of adults in households with children said it was something or very difficult to pay normal household expenses during the pandemic, a higher proportion than adults without children (Aug. %) (26%). Figure 2). The proportion of households with children who sometimes or often did not have enough to eat rose during the pandemic. 10% of these households reported insufficient groceries before March 13, compared with 12% on August 31. Food insufficiency is particularly pronounced in black (20%) and Latin American (16%) households with children compared to white (9%) households. In addition, more than a third (34%) of adults in households with children reported little or no confidence in their ability to pay rent the next month (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Households with children report a high rate of problems meeting basic needs during the pandemic.

School closings can further reduce the ability of low-income children to access food through free and discounted school meals. A little more than every third student between the ages of 5 and 17 is entitled to a free or inexpensive meal. Because these students are often dependent on school for two meals a day, school closings can limit their ability to eat regularly and gain access to nutritious foods. States and municipalities are working to continue school lunches under US Department of Agriculture exemptions that allow them to offer meals under the Summer Food Service Program or the Seamless Summer Option, and through new powers to expand the availability of these programs. However, research shows that only a small proportion (15%) of the nearly 30 million children who received meals through the program prior to the pandemic continue to do so.

Health risks due to health and social disorders

Preliminary reports, based on harm data, show a significant decrease in service use among Medicaid / CHIP beneficiaries under 18 between January and May 2020, possibly due to social distancing measures and exposure concerns (Figure 3) . Before the pandemic, preventive and basic health care utilization among children was generally high: in 2018, the vast majority (96%) of children had regular health care, almost 90% had seen a good child in the past and only had one year a small part (2.5%) delayed the maintenance due to cost reasons. However, an early analysis of the claims data by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) shows significant decreases in the use of regular and preventive measures. For Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries under 2 years of age, vaccination rates fell by almost 34% between January and May 2020. Other benefits, such as child screening services, dental services, and outpatient psychiatric services, declined 50% or more between January and May 2020 for Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries aged 18 and under (Figure 3). Other administrative data across payers shows a significant drop in vaccine orders and administration, especially among children over 24 months old, with cumulative doses of non-influenza vaccines ordered by mid-April 2020 by more than 3 million from the same point in time in 2019 went back. Parents can experience delays in care due to health concerns or private insurance costs and providers may have limited capacity due to changes in operations to safely treat patients.

Figure 3: Use of Medicaid / CHIP child benefits services that declined in the first few months of the pandemic

Although some data shows that the use of telemedicine services among children increased during the pandemic, it did not offset the decline in in-person visits. A July 2020 study found that prior to the pandemic, only 15% of pediatricians reporting on telemedicine and many pediatric practices had to adapt quickly to provide telemedicine services during the pandemic. Medicaid, which insures nearly 40% of children in the United States, allows telemedicine to be used for Medicaid-funded visits and services for children, but as of July 23, only 15 states had issued telemedicine guidelines for child health. Nursing and EPSDT visits, and 16 states had issued guidelines to providers to enable the provision of telemedicine or remote care for early childhood intervention services. Preliminary reports from CMS, based on Medicaid, show that the delivery of telemedicine services to children increased by over 2,500% from February to April 2020. However, these increases did not offset the decline in face-to-face visits, and usage continued to decline significantly for many services.

Challenges in accessing health services are particularly problematic for the EU 13 million children with special health needs (CSHCN). Children with special health needs due to mental / developmental disorders, physical disabilities and / or mental disabilities require ongoing care and special services. These disabilities can include asthma, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, muscular dystrophy, brain injury, or epilepsy. Many of these children are in need of ongoing care, especially those who have ongoing complications or who have recently had procedures. However, due to social distancing rules and the risk of exposure in healthcare, CSHCN may forego necessary care. In addition, CSHCN and their families rely on home health care to complement other sources of care. This includes children with particularly complex care needs who may need care to live safely at home with a tracheostomy or feeding tube. Given the staff shortages and other complications caused by the pandemic, home care and support services may no longer be an option for many families.

Die Pandemie hat dazu geführt, dass viele Dienste in Kinderhilfesystemen gekürzt oder verschoben wurden, was zu Bedenken hinsichtlich vermehrten Kindesmissbrauchs und verminderter Berichterstattung führte. Viele Kinderhilfswerke haben die persönlichen Inspektionen von Häusern eingeschränkt, wodurch gefährdete Kinder einem noch größeren Risiko für Missbrauch und Vernachlässigung ausgesetzt sind. Fachleute für Kinderfürsorge berichten auch von Besorgnis darüber, dass die Pandemie angesichts des zunehmenden Stresses für Familien und berufstätige Eltern zu einer Zunahme von Kindesmisshandlung und Vernachlässigung führen wird. Es gibt auch Bedenken hinsichtlich einer verminderten Meldung von Kindesmissbrauch und Vernachlässigung, die sich aus Maßnahmen zur sozialen Distanzierung ergeben könnten. In Staaten wie Wisconsin, Oregon, Pennsylvania und Illinois gingen die Berichte über Kindesmissbrauch im März zwischen 20% und 70% zurück, was wahrscheinlich darauf zurückzuführen ist, dass Kinder von Orten ferngehalten werden, an denen Fachkräfte geschult sind, um Szenarien zu identifizieren und zu melden Kindesmisshandlung und Vernachlässigung. Die Pandemie kann auch zu einem erhöhten Bedarf an Kinderhilfsdiensten führen, da sich ein erhöhter finanzieller Druck auf Familien negativ auf die Beziehungen der Eltern zu ihren Kindern auswirkt. Dieser zusätzliche Bedarf könnte nicht gedeckt werden, da das Kinderhilfesystem mit den zusätzlichen Komplikationen von COVID-19 Schwierigkeiten hat, seine derzeitige Fallzahl und bedürftigen Familien zu bewältigen.

looking ahead

Die Coronavirus-Pandemie ist ein beispielloses Ereignis im Leben der meisten Menschen und führt zu einem außerordentlich hohen Risiko für Gesundheit und Wohlbefinden. Das geringere Risiko von Kindern für schwere Krankheiten aufgrund von COVID-19 hat die meisten Diskussionen und politischen Debatten über die Pandemie dazu geführt, sich auf Erwachsene mit hohem Risiko zu konzentrieren, obwohl die jüngste Debatte über Schuleröffnungen den Schwerpunkt auf die Gesundheit und das Wohlbefinden von Kindern verlagert hat. Da viele Schulen wiedereröffnet werden, kann die Verfolgung von Fällen und schweren Krankheiten bei Kindern sowie das Verständnis, wer dem höchsten Risiko ausgesetzt ist, den politischen Entscheidungsträgern helfen, Bildungs- und Unterstützungssysteme zu entwickeln, um Exposition, Risiko und Krankheit zu minimieren. Darüber hinaus sind viele Kinder bereits mit erheblichen Zugangsbarrieren, emotionalen Belastungen und finanziellen Schwierigkeiten konfrontiert, die langfristige Auswirkungen auf ihr Leben haben könnten. Diese Analyse unterstreicht, wie wichtig es ist, sichere Ansätze für die Eröffnung von Schulen zu verfolgen, um die körperliche und emotionale Gesundheit in Einklang zu bringen. Richtlinien zur Erleichterung der Aufnahme in die Krankenversicherung, zur Gewährleistung des Zugangs zu Gesundheitsdiensten, insbesondere zu verhaltensbezogenen Gesundheitsdiensten, sowie zur Erleichterung des Zugangs zu Sozialdiensten zur Unterstützung von Familien mit Kindern können dazu beitragen, einige der Konsequenzen anzugehen, mit denen Kinder derzeit konfrontiert sind.

Comments are closed.