Vaccine Hesitancy in Rural America

The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is an ongoing research project that tracks public attitudes and experiences with COVID-19 vaccinations. Using a combination of surveys and focus groups, this project will track the dynamics of public opinion as vaccine development progresses, including the trust and reluctance of the vaccine, trusted ambassadors and messages, and the public's experience of vaccination at the beginning of its dissemination.

Vaccine Reluctance in Rural America

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were felt in communities across the United States, from the largest urban centers to the smallest rural communities. As previous research has shown, rural communities are facing unique challenges in responding to the pandemic due to the lack of medical staff, fewer hospital beds per capita, limited access to telemedicine, and populations at risk for age or age Deaths from COVID-19 have a chronic disease prevalence. In addition, a previous KFF analysis found that non-metro counties saw a faster rate of growth in the spread of the virus, and newer data confirms it is still the case. In late 2020, there were tons of reports on the rural communities hardest hit by the coronavirus, including remote villages in Alaska and ranches in Texas. An analysis by the Pew Research Center found that sparsely populated rural areas caused twice as many coronavirus-related deaths than urban areas.

The December KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor results are cause for concern as the number of pandemics hit rural communities hard. Rural residents, along with Republicans, people aged 30 to 49 and black adults, are among the most hesitant groups to get vaccinated. People who live in rural areas in the US are significantly less likely to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, which is considered safe and free, than people who live in suburbs and cities in America. Three in ten (31%) people in rural areas say they will “definitely get” the vaccine, compared with four in ten people in urban areas (42%) and suburbs (43%). Another third of people in rural areas say they are “likely to get” it, while 35% say they either “probably won't” (15%) or “definitely won't” (20%).

Figure 1: Smaller proportions of rural residents say they will definitely get a COVID-19 vaccine

There are many factors linked to a person's willingness to receive the coronavirus vaccine, including their age, educational level, and especially their identification as a political party. For example, the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor finds that Republicans are much less likely to say they will be given a coronavirus vaccine compared to their independent and Democratic counterparts. Even when we take these factors into account, people who live in rural areas are still more likely to be reluctant to vaccinate than people who live in suburbs and urban areas.

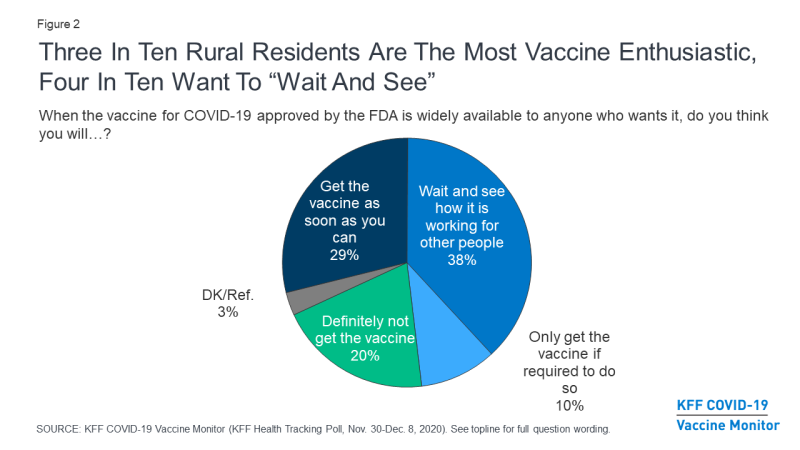

Given that news of the coronavirus vaccine is slow to reach hospitals and healthcare workers in rural communities, three in ten rural residents (29%) are most enthusiastic about receiving the vaccine, according to KFF data, saying that they will receive the COVID. 19 vaccine "as soon as possible" (compared to 36% of urban residents and 34% of suburban residents). Another four in ten (38%) rural residents say they will wait to get the vaccine, and one in ten says they will only receive the vaccine if they need to do it for work or other activities.

Figure 2: Three out of ten rural dwellers are most enthusiastic about vaccines, four out of ten want to "wait and see"

What Are the Effective Messages and Ambassadors for Rural Americans?

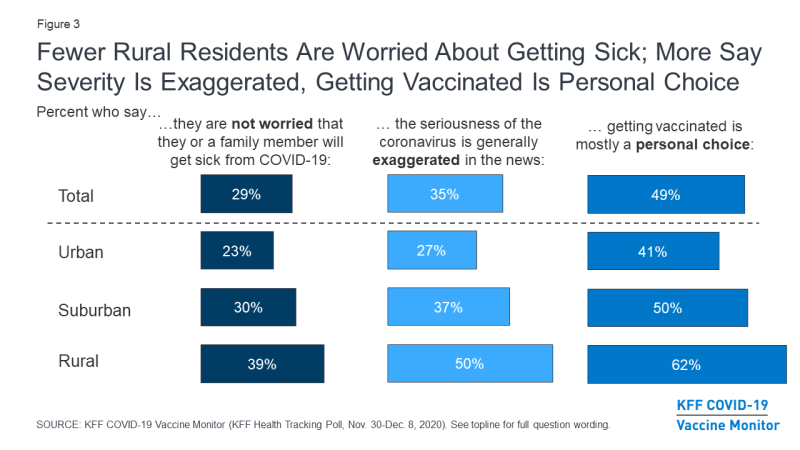

If partisan identification and demographics do not fully explain the greater hesitation, what is driving rural people's attitudes towards a vaccine? While rural residents are just as likely as people in urban and suburban communities to know someone who tested positive or died of coronavirus, four in ten rural residents (39%) say they don't fear they or anyone in their family will get sick from Coronavirus compared to 23% of city dwellers and three in ten suburban residents (30%). In addition, half of rural residents say the severity of the coronavirus is "generally exaggerated" compared to 27% of urban residents and 37% of suburban residents.

For rural residents, getting a COVID-19 vaccine is more of a personal choice (62%) than part of “everyone's responsibility to protect the health of others” (36%). A majority of urban residents (55%) say vaccination is part of everyone's responsibility, as does nearly half of suburban residents (47%).

Figure 3: Fewer rural residents are concerned about getting sick; Say more, the severity is exaggerated, vaccination is a personal choice

When it comes to reaching out to rural residents, a large majority of rural Americans (86%) say they trust their own doctor or health care provider to provide reliable information about a COVID-19 vaccine. Smaller stocks say the FDA (68%), the CDC (66%), their local health department (64%), Dr. Trusting Fauci (59%) or government officials (55%).

Rural residents' hesitation about vaccines is more than just partiality and is closely related to their views on the severity of the coronavirus and the reasons for vaccination. Effective messages must be delivered by trusted messengers and incorporate these strong beliefs in order to achieve successful vaccine uptake in rural America.

Comments are closed.