KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: December 2020

The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is an ongoing research project that tracks public attitudes and experiences with COVID-19 vaccinations. Using a combination of surveys and focus groups, this project will track the dynamics of public opinion as vaccine development progresses, including the trust and reluctance of the vaccine, trusted ambassadors and messages, and the public's experience of vaccination at the beginning of its dissemination.

Main results

- With the launch of the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor, a new KFF survey found an increase in the proportion of the public who said they would definitely or likely receive a vaccine for COVID-19 if it was deemed safe and available by scientists would be free to anyone who wanted it. That percentage is now 71%, up from 63% in a September poll conducted in collaboration with ESPN's The Undefeated. Following the presidential election and promising news about several COVID-19 vaccine candidates, the new poll shows a surge in the proportion who said they would be vaccinated across races and ethnic groups, and among Democrats and Republicans (willingness to get vaccinated) among independents not changed).

- About a quarter (27%) of the public continues to hesitate about vaccines, saying that they would likely or definitely not receive a COVID-19 vaccine, even if it were available free of charge and considered safe by scientists. Reluctance to vaccinate is highest among Republicans (42%), 30-49 year olds (36%), and rural residents (35%). Importantly, 35% of black adults (a group that has borne a disproportionate burden from the pandemic) say they would definitely or probably not be vaccinated, as do a third of those who say they have been classified as essential workers his (33%) and three in ten (29%) of those who work in a health care system.

- Among those who are reluctant to get a COVID-19 vaccine, the main reasons are concerns about possible side effects (59% cite this as the main reason) and a lack of trust in the government to ensure the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines %)), Concerns that the vaccine is too new (53%), and concerns about the role of politics in the development process (51%). About half of black adults who say they likely or definitely not to be vaccinated cite the main reasons that they generally do not trust vaccines (47%) or fear getting COVID-19 from the vaccine (50%) ), suggesting that fighting certain types of misinformation messages may be especially important in building vaccines' confidence in this group.

- A large majority (71%) of the public believe that a vaccine will be available to anyone who wants it in the US by summer 2021. That includes about three in ten who believe it will be available either earlier by the end of 2010, 2020 or early 2021. Despite promising news about vaccines from Pfizer / BioNTech and Moderna, expectations for this group must, given the small number of starting doses available, and the barriers to making and distributing sufficient doses of vaccine for all may be eased in the United States.

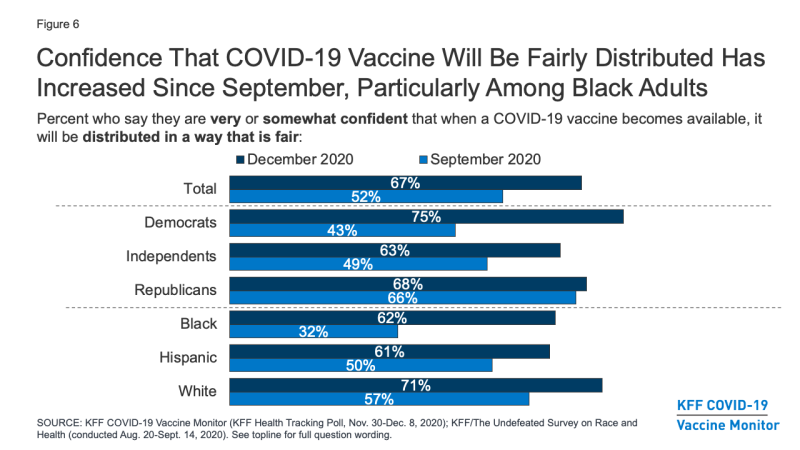

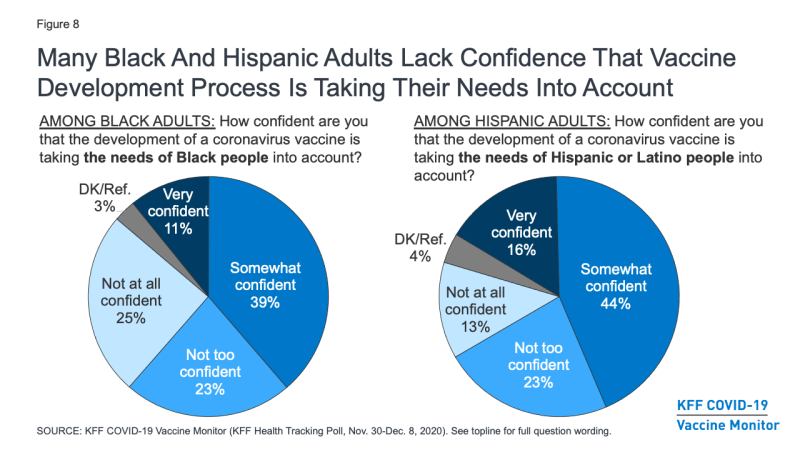

- A critical issue that policy makers are already facing is how to prioritize different groups and ensure fair distribution of the vaccine. Public confidence on this issue has increased significantly in recent months, particularly among black Americans. Two-thirds of the public are now at least reasonably confident that a COVID-19 vaccine, once it becomes available, will be fairly distributed, up from about half (52%) in September. Among black Americans, the proportion has almost doubled from 32% to 62%. However, concerns remain as to whether the needs of people of color will be taken into account in the development of the vaccine. About half (48%) of black adults say they aren't sure that developing a COVID-19 vaccine will meet the needs of black people, and over a third (36%) of Hispanic adults say the same about the needs of Hispanic people.

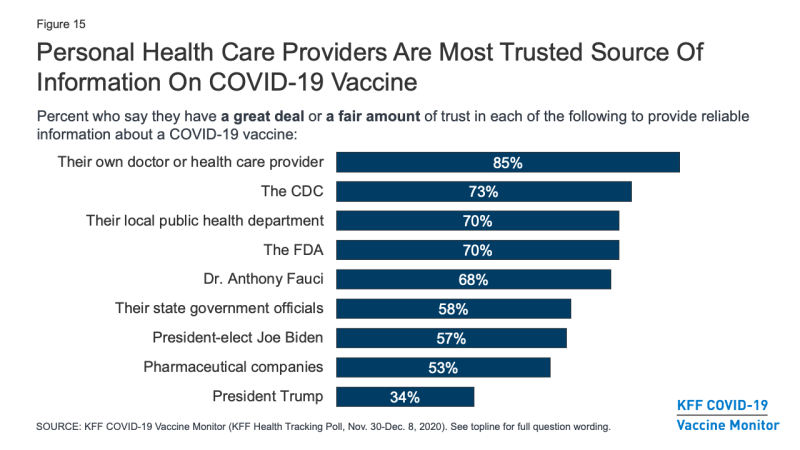

- Understanding who the public trusts for reliable vaccine information is critical to any effort to spread COVID-19 vaccination. The survey found that, as with many health topics, people's personal health care providers are the most trusted source of information about COVID-19 vaccines. 85% say they trust their own doctor or health care provider at least an adequate amount for reliable vaccines for information. Some local, state, and national messengers – including the CDC, FDA, Dr. Anthony Fauci and state and local health officials – also trust the majority of the public, but trust in these government-related sources is somewhat divided on party lines Democrats tend to express higher levels of trust than Republicans.

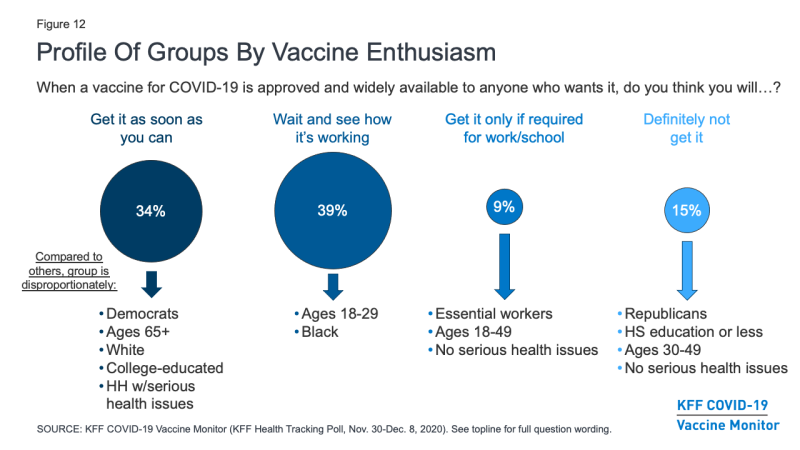

- The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor also tracks the public's excitement for vaccination and identifies four groups of people who may need different communication strategies for a COVID-19 vaccine. These include: the "as soon as possible" group (34% of the public), who say that an approved and widely available vaccine will receive it as soon as possible; the “wait and see” group (39%) who said they will wait and see how the vaccine works for other people before getting themselves vaccinated; the “only when needed” group (9%) who said they were only vaccinated when needed for work, school or other activities; and the “definitely not” group (15%) who said they were definitely not going to get a vaccine, even if it was considered free and safe by scientists. This last group is likely to be the hardest to convince because they have low trust in public health messengers, very low flu vaccination rates, and high rates of misinformation about other public health measures such as wearing masks.

COVID-19 Vaccine Reluctance: Trends, Reasons, and Subgroups

The proportion of the public willingness to be vaccinated for COVID-19 has increased

The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor notes that the proportion of the public who say they would definitely or likely get a vaccine for COVID-19 if it was found safe by scientists and made available for free to anyone who wanted it stands, up slightly since September following presidential election results and promising news about several COVID-19 vaccine candidates. In the new survey, seven in ten (71%) said they would definitely (41%) or likely (30%) receive such a vaccine, while around a quarter (27%) said they would likely (12%) ) or definitely (15%) do not understand. The proportion that said they would definitely or likely be vaccinated is 8 percentage points higher than a KFF survey conducted in September by ESPN in collaboration with The Undefeated (from 63% to 71%), while the proportion that says they would definitely or probably not be vaccinated increased by 8 percentage points by 7 percentage points (from 34% to 27%).

Figure 1: The statement that they would get a COVID-19 vaccine if it was free and considered safe by scientists has increased since September

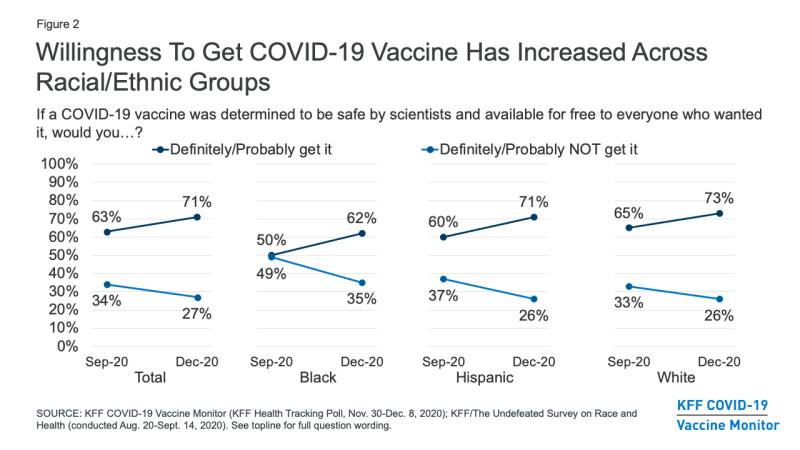

In terms of races and ethnic groups, vaccination readiness has increased among black, Hispanic, and white adults alike. The change is perhaps most dramatic in black adults, who increased vaccination readiness from 50% in September to 62% in December. While black adults were roughly evenly divided in September about whether they would get a COVID-19 vaccine, which has been considered free and safe by scientists, they now say they would be vaccinated almost twice as often as they would not (62% versus 35%).

Figure 2: Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccines has increased across all racial / ethnic groups

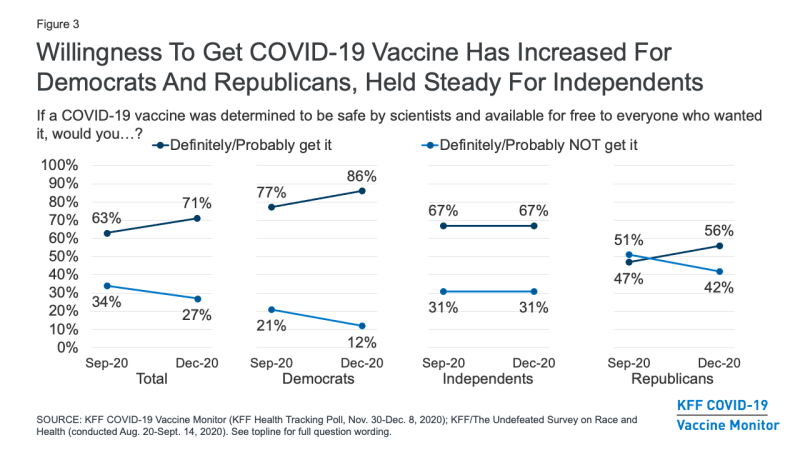

While a large partisan gap remains, willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 has increased for both Democrats (from 77% in September to 86% in December) and Republicans (from 47% to 56%) but remained the same among independents (67%).

Figure 3: Willingness to get COVID-19 vaccines has increased for Democrats and Republicans, held constant for independents

A quarter remain reluctant to get a COVID-19 vaccine, including four in ten Republicans

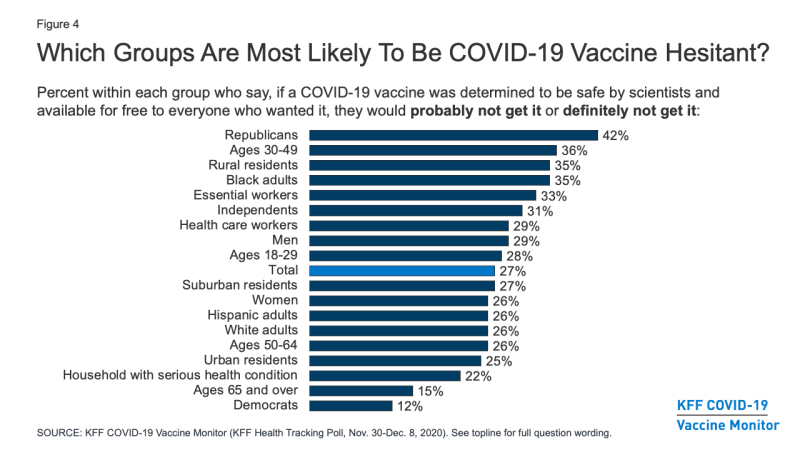

About a quarter (27%) of the public continues to hesitate about vaccines, saying that they would likely or definitely not receive a COVID-19 vaccine, even if it were available free of charge and considered safe by scientists. Reluctance to vaccinate is highest among Republicans (42%), 30-49 year olds (36%), and rural residents (35%). Importantly, 35% of black adults (a group that have borne a disproportionate burden from the pandemic) say they would definitely or probably not be vaccinated, as do a third of those who say they are considered essential workers , and three in ten (29%) of those who work in a health care system.

Figure 4: Which Groups Are Most Likely to be COVID-19 Vaccine Reluctant?

Different groups have different reasons for the reluctance of COVID-19 vaccines

Among those who are reluctant to get a COVID-19 vaccine, the main reasons are concerns about possible side effects (59% cite this as the main reason) and a lack of trust in the government to ensure the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines %)), Concerns that the vaccine is too new (53%), and concerns about the role of politics in the development process (51%). Around four in ten say the risks of COVID-19 are exaggerated (43%) or that they generally do not trust vaccines (37%), while around a third say they do not trust the healthcare system (35%) and smaller proportions say they fear getting COVID-19 from the vaccine (27%) or they don't think they could get sick from the virus (20%).

Among the reluctant vaccines, members of different racial groups have different reasons not to be vaccinated. For example, black adults who are reluctant to get the vaccine are more likely than white adults to cite concerns about side effects (71% versus 56%) and vaccine novelty (71% versus 48%) as the main reasons for not wanting to be vaccinated. Importantly, about half of black adults who say they likely or definitely not to be vaccinated are the main reasons they fear getting COVID-19 from the vaccine (50%) or that they have vaccines in general do not trust (47%), suggesting that fighting certain types of misinformation messages can be especially important in building vaccines' trust in this group.

The reasons for the vaccine hesitation also differ somewhat in the identification of the partisans. Among Republicans who say they won't get vaccinated is a primary reason they think the risks of COVID-19 are exaggerated, as reported by 57% of Republicans who hesitate to vaccinate (24% of all Republicans) Main reason is mentioned.

| Among those who definitely would not or probably would not be vaccinated: Percent who say any of the following is a Main reason Why: | total | Party ID | Age | Race / ethnicity | |||

| Independently | republican | 18-49 | 50+ | black | White | ||

| Concerned about possible side effects | 59% | 59% | 54% | 58% | 63% | 71% | 56% |

| Don't trust the government to make sure the vaccine is safe and effective | 55 | 52 | 56 | 55 | 53 | 58 | 54 |

| The vaccine is too new and would like to see how it works in other people | 53 | 54 | 41 | 57 | 46 | 71 | 48 |

| Politics has played too much of a role in the vaccine development process | 51 | 46 | 53 | 47 | 59 | 54 | 49 |

| The risks of COVID-19 are exaggerated | 43 | 40 | 57 | 40 | 51 | 33 | 49 |

| In general, don't trust vaccines | 37 | 43 | 31 | 37 | 38 | 47 | 36 |

| Don't trust the health system | 35 | 34 | 36 | 32 | 42 | 28 | 36 |

| Concerned they might get COVID-19 from the vaccine | 27 | 30th | 18th | 26th | 26th | 50 | 21st |

| Don't think that COVID-19 puts you in danger of getting sick | 20th | 18th | 23 | 18th | 26th | 20th | 19th |

| NOTE: The sample size is too small to be separated from Democrats and Hispanics who say they will definitely or probably not be vaccinated. See Appendix A for tables based on the grand total. | |||||||

COVID-19 Vaccine Trust and Expectations

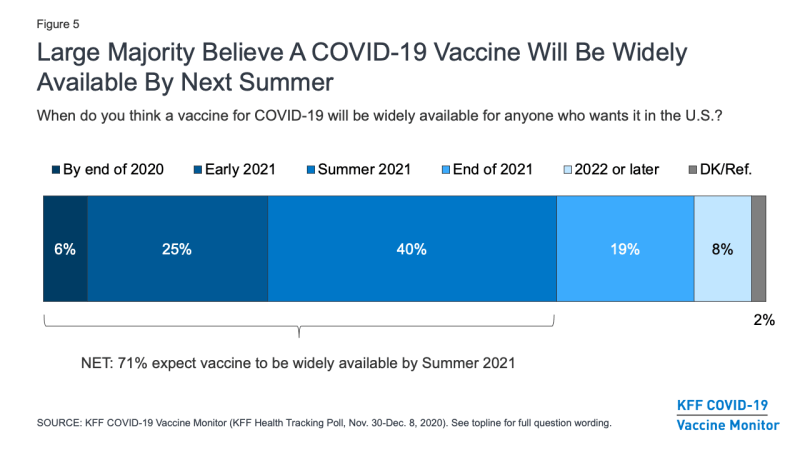

A large majority (71%) of the public believe that a vaccine will be available to anyone who wants it in the US by summer 2021. That includes about three in ten who believe it will be available either earlier by the end of 2010, 2020 or early 2021. About a quarter (26%) of the population are more skeptical and believe that a vaccine will not be available until late 2021 or sometime will be generally available in 2022.

Figure 5: Large majority believe that a COVID-19 vaccine will be widely available by next summer

A critical issue that policy makers are already facing is how to prioritize different groups and ensure fair distribution of the vaccine. Public confidence on this issue has increased significantly in recent months, particularly among black Americans. Two-thirds of the population are now at least reasonably confident that a COVID-19 vaccine, once it becomes available, will be fairly distributed, up from around half (52%) in September (before the presidential election) and positive news about multiple vaccine candidates ). Among black Americans, the proportion has almost doubled from 32% to 62%.

Figure 6: Confidence that the COVID-19 vaccine will be distributed fairly has increased since September, especially among black adults

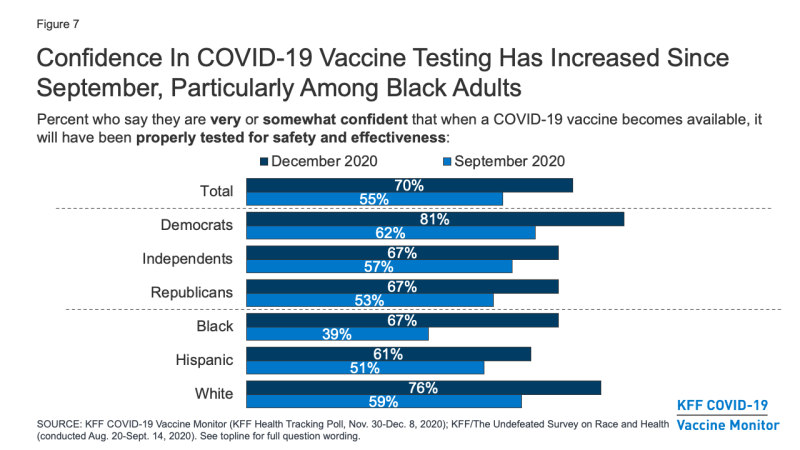

Similarly, compared to September, a larger segment of the public says they are very or somewhat confident that once a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available, it has been properly tested for safety and effectiveness (70% versus 55% in September ). . Again, the increase was most pronounced among black Americans (67% versus 39%).

Figure 7: Confidence in COVID-19 vaccine tests has increased since September, especially among black adults

However, concerns remain as to whether the needs of people of color will be taken into account in the development of the vaccine. About half (48%) of black adults say they aren't sure that developing a COVID-19 vaccine will meet black people's needs (up from 65% in September), and over a third (36%) are Hispanic adults say the same thing about the needs of Hispanics.

Figure 8: Many Black and Hispanic adults lack confidence that the vaccine development process will address their needs

Other COVID-19 vaccine settings

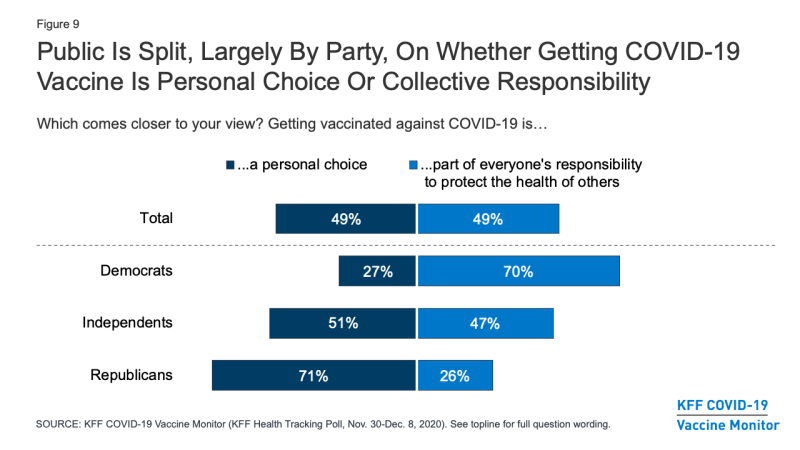

The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor also tracks other attitudes related to vaccination and examines the relationship of these attitudes to vaccine hesitation. One question that is having an impact on vaccine news is whether people believe vaccination is more a matter of individual freedom or collective responsibility. The latest poll found that the public is evenly distributed. About half (49%) say vaccinating against COVID-19 is "a personal choice" and the other half (49%) say that "everyone's responsibility to protect the health of others rests with others." Partisans differ on this issue, with seven in ten Democrats saying vaccination is part of everyone's responsibility to protect public health, and a similar proportion of Republicans (71%) say it is a personal choice As shown below, these settings are related to people's personal plans to receive a COVID-19 vaccine when one becomes available.

Figure 9: The public is largely divided by party, whether it is a personal choice or a collective responsibility to receive a COVID-19 vaccine

With the name "Operation Warp Speed" given to the US COVID-19 vaccine development effort, there were early concerns that the public would have no confidence in a vaccine that they could consider to be quickly on the market. In fact, a September and October poll by the KFF found that many adults in the US were concerned that the FDA would approve a vaccine under political pressure from Trump's White House. However, the most recent poll found that around two-thirds of the public (64%) – including similar proportions of Democrats, Republicans, and Independents – believe that vaccine development and testing is moving at the right pace, even though small stocks say that it is moving too fast (22%) or too slow (12%).

Figure 10: Despite early concerns, most are now sensing that the COVID-19 evolutionary process is moving at the right rate

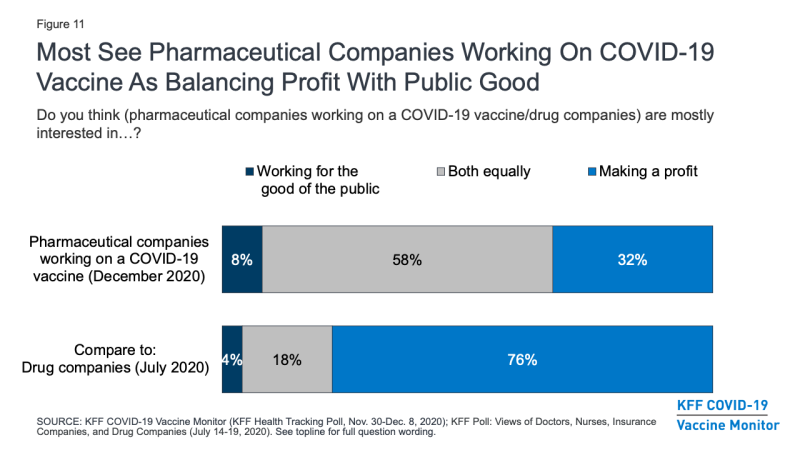

The financial motives of pharmaceutical companies have also been cited as a potential barrier to public confidence in a COVID-19 vaccine. The survey suggests that typically sharp public views about these companies' profit motives may be fading somewhat in the face of the pandemic. A KFF poll earlier this year, asking about "pharmaceutical companies" in general, found that three-quarters (76%) of the public believed that these companies were primarily interested in making a profit, while smaller stocks said primarily in a work for the good of the public (4%) or about equally motivated by profits and the common good (18%). The December survey looked more specifically at “pharmaceutical companies working on a COVID-19 vaccine” and found that most (58%) said these companies were equally interested in working for the common good and making a profit While the proportion who saw gains your main motivation was much lower (32%).

Figure 11: Most see pharmaceutical companies working on COVID-19 vaccines as a balance between profit and the public good

Profiles of the public by vaccine enthusiasm levels

The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor has also measured public enthusiasm for vaccination and identified four groups of people who may need different communication strategies for a COVID-19 vaccine. (For more information on the demographics of each of these groups, see Appendix B.)

Around a third of the public (34%) belong to the “as soon as possible” group, which says that when a vaccine is approved and widely available, it is received as soon as possible. This group disproportionately consists of Democrats (43% versus 32% of the total population), adults aged 65 and over (33% versus 21%), white adults (71% versus 61%) and college graduates (39% versus 31%) and those who who are in serious health or who live with someone who does (52% versus 46%). Because of their willingness to get vaccinated, some people in this group may be frustrated with the pace of vaccine distribution if they do not fall into one of the priority groups for early vaccination. Messages that highlight the reasons for prioritizing different groups can be important to that group.

About four in ten (39%) of the public belong to the group “wait and see”. These people are a mix of those who say they'll definitely or probably will be vaccinated and those who say they probably won't – but all of them say if a vaccine becomes widely available they'll wait to see one While it is available to see how it works for other people before vaccinating yourself. This group looks very much like the general public, but somewhat represents young adults ages 18-29 (28% versus 21% of the general population) and black adults (16% versus 12%). The ultimate willingness to be vaccinated in this group depends to a large extent on the coverage of events that occurred during the early introduction of the vaccine to priority populations. What they hear and learn about side effects, effectiveness, and access to the vaccine will be important in making their final decisions about whether and when to get vaccinated. This group is also likely to be the most dynamic in the early stages of the rollout, and may shift their responses between “likely to be” and “likely not to be” vaccinated if the presentation of the COVID-19 vaccine changes.

The smallest group – 9% of the public – says they are only vaccinated when necessary for work, school or other activities. This group is slightly younger than the general population (74% are under 50, compared with 54% of all adults). Importantly, around six in ten members of this group (61%) say they have been classified as essential workers, which means they will have to work outside of their home during the pandemic. Despite being so small, the fact that such a large proportion of this group belong to a high risk category for exposure to coronavirus makes them an important group for increasing vaccine confidence.

After all, 15% of the public falls into the group that is most resistant. Those who say they would definitely not get a COVID-19 vaccine even if it were found to be safe by scientists and made available for free. This group is disproportionately made up of Republicans (41% versus 25% of the population) and those with no additional education beyond high school (53% versus 38%). It also represents something for people aged 30-49 years (46% versus 33%). This group is the most skeptical and possibly the most difficult to reach with pro-vaccine news.

Figure 12: Profile of the groups according to enthusiasm for vaccination

In other words, the proportion of the public that falls into each of these groups differs based on bias and racial and ethnic background. For example, about half of black adults (52%) fall into the wait and see group compared with about four in ten Hispanic adults (43%) and just over a third of white adults (36%). In contrast, white adults (40%) are more likely than black adults (20%) or Hispanic adults (26%) to be in the “as soon as possible” group.

In partisan groups, nearly half of Democrats (47%) fall into the “as soon as possible” category, compared with about three in ten Independents (30%) and Republicans (28%). And while the majority of partisan groups fall into one of the first two categories, a quarter of Republicans and 17% of Independents say they will definitely not get the vaccine, much higher than the Democratic percentage (5%).

| Percent who say when a vaccine for COVID-19 is FDA approved and widely available to anyone who wants it, they will: | total | Party ID | Race / ethnicity | ||||

| Dem. | Ind. | Rep. | black | Hispanic | White | ||

| Get the vaccine asap | 34% | 47% | 30% | 28% | 20% | 26% | 40% |

| Wait for it to be available for a while to see how it works for other people | 39 | 41 | 38 | 33 | 52 | 43 | 36 |

| Only get the vaccine if necessary for work, school, or other activities | 9 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 7th |

| Definitely not getting the vaccine | 15th | 5 | 17th | 25th | 15th | 18th | 15th |

| Don't know / Declined | 3 | 2 | 4th | 4th | 3 | 2 | 3 |

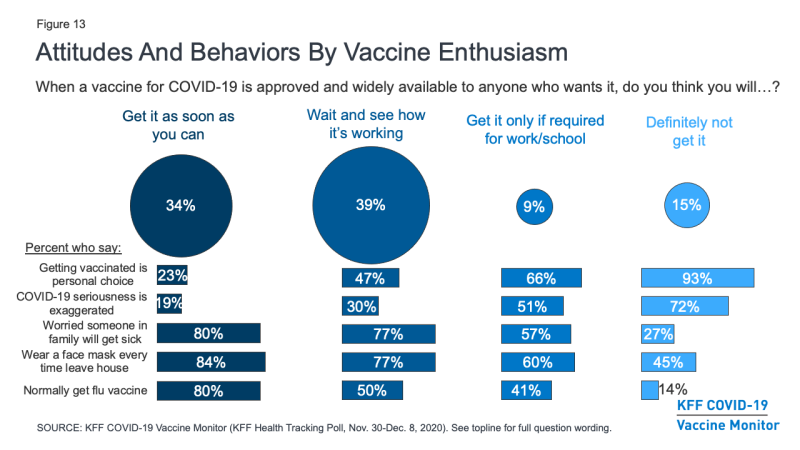

These groups differ not only in their demographics, but also in many of their attitudes and behaviors. For example, the vast majority (93%) of those who say they definitely will not be vaccinated and two-thirds (66%) of those who say they will only be vaccinated when it is necessary for work or school than Vaccinated against COVID-19 personal choice, compared with around half (47%) of the group “wait and see” and only a quarter (23%) of the group “as soon as possible”. The more reluctant groups are also far more likely than the more enthusiastic groups to say that the seriousness of COVID-19 in the news is generally exaggerated. Conversely, around eight in ten in the group say “as soon as possible” (80%) and “wait and see” (77%) that they are very or somewhat concerned that they or someone in their family will develop COVID. 19, compared with about six out of ten in the “only if needed” group (57%) and only a quarter (27%) in the “definitely not” group.

Figure 13: Attitudes and behavior through enthusiasm for vaccinations

Behavior with non-coronavirus vaccines and other protective measures also differs between these groups. For example, about eight in ten in the groups that accept more vaccines say they wear a face mask and may be in contact with other people every time they leave the house, compared with about six in ten in the “only if necessary ”and less than half (45%) in the group“ definitely not ”. There is also a linear relationship between enthusiasm for vaccines and the percentage of those who say they usually get a flu vaccine every year, from 80% in the "as soon as possible" group to just 14% in the "definitely" group Not".

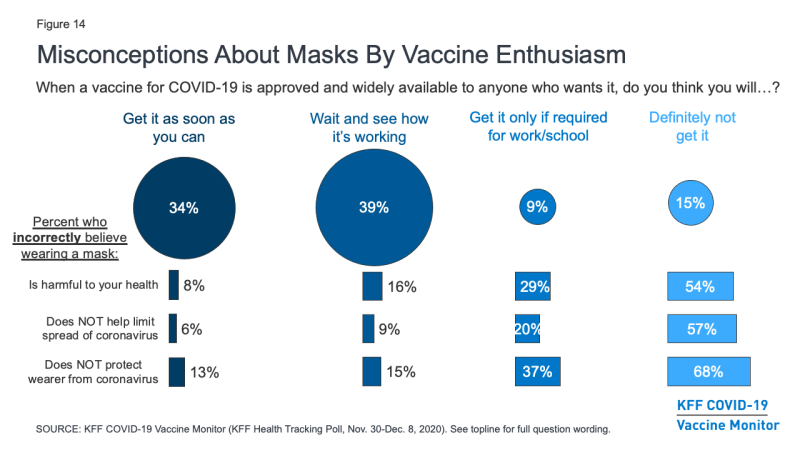

Importantly, the survey also suggests that those who are more reluctant to get vaccinated against COVID-19 are more likely to have misconceptions about other important public health actions. For example, about two-thirds (68%) of those who say they definitely won't get vaccinated, and nearly four in ten (37%) of those who say they only get it when necessary, believe wearing a face mask does not help protect the wearer from coronavirus. Similarly, more than half (54%) of the "definitely not" group and three in ten (29%) of the "only when necessary" group believe that wearing a face mask is harmful. Given that the basic public health news about the benefits of wearing masks for many of these individuals has not broken through, novel strategies may be needed to connect with them during the vaccination work.

Figure 14: Misunderstandings about masks due to enthusiasm for vaccinations

Trustworthy messengers

As vaccination efforts continue, the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor will keep track of which messengers are the most trusted sources of vaccine information to the public. The most recent survey found that, as with many health issues, people's personal health care providers are high on the list, ahead of any national, state, or local messenger. More than eight in ten (85%) say they trust their own doctor or health care provider "a lot" or "an adequate amount" to provide reliable information about a COVID-19 vaccine. About seven in ten also trust national messengers such as the US CDC (73%), the FDA (70%) and Dr. Anthony Fauci (68%) as well as her local health department (70%). Slightly fewer, but still the majority, trust their government officials (58%), President-elect Joe Biden (57%) and pharmaceutical companies (53%) at least adequately, while only 34% say so trust President Trump.

Figure 15: Personal health care providers are the most trusted source of information about COVID-19 vaccines

Reliance on personal doctors for vaccine information is generally high for partisan identification and race / ethnicity. Wenn es jedoch um mit der Regierung verbundene Informationsquellen wie die CDC und sogar die örtlichen Gesundheitsämter geht, gibt ein viel größerer Anteil der Demokraten im Vergleich zu den Republikanern an, dass sie darauf vertrauen, dass jeder zuverlässige Informationen über einen COVID-19-Impfstoff liefert, wobei die Unabhängigen im Allgemeinen in die Mitte fallen. Vorhersehbarerweise sinkt das Vertrauen in den gewählten Präsidenten Biden und Präsident Trump stark nach parteipolitischen Maßstäben.

| Prozent, die sagen, dass sie jedem der folgenden Punkte vertrauen much or eine angemessene Menge um zuverlässige Informationen über einen COVID-19-Impfstoff bereitzustellen: | Gesamt | Party ID | Rasse / ethnische Zugehörigkeit | ||||

| Dem. | Ind. | Rep. | Schwarz | Hispanic | Weiß | ||

| Ihr eigener Arzt oder Gesundheitsdienstleister | 85% | 93% | 84% | 81% | 85% | 75% | 87% |

| Die US-amerikanischen Zentren für die Kontrolle und Prävention von Krankheiten oder CDC | 73 | 88 | 70 | 57 | 78 | 71 | 73 |

| Die US-amerikanische Food and Drug Administration oder FDA | 70 | 81 | 67 | 62 | 74 | 66 | 71 |

| Ihr örtliches Gesundheitsamt | 70 | 87 | 67 | 56 | 79 | 65 | 70 |

| Dr. Anthony Fauci, der Direktor des Nationalen Instituts für Allergien und Infektionskrankheiten | 68 | 90 | 67 | 47 | 77 | 62 | 68 |

| Ihre Regierungsbeamten | 58 | 77 | 53 | 47 | 65 | 53 | 60 |

| Gewählter Präsident Joe Biden | 57 | 93 | 52 | 23 | 76 | 58 | 54 |

| Pharmaunternehmen | 53 | 67 | 48 | 45 | 58 | 50 | 54 |

| Präsident Trump | 34 | 7 | 30th | 78 | 12 | 26th | 41 |

Vertrauenswürdige Boten unterscheiden sich je nach Impfbegeisterung auch zwischen den verschiedenen Profilgruppen. Die am einfachsten zu überzeugende Gruppe – diejenigen, die sagen, dass sie den Impfstoff so bald wie möglich erhalten werden – setzt mit Ausnahme von Präsident Trump ein hohes Maß an Vertrauen in jede Art von Boten, nach der gefragt wird. Die Gruppen „abwarten und sehen“ und „nur bei Bedarf“ setzen beide das höchste Maß an Vertrauen in ihre eigenen Gesundheitsdienstleister, aber die Mehrheit dieser beiden Gruppen gibt auch an, dass sie einer Vielzahl nationaler und lokaler Boten vertrauen, einschließlich der CDC und der FDA , Dr. Anthony Fauci und ihre örtlichen Gesundheitsämter. Die Gruppe „nur wenn erforderlich“ ist politisch etwas gespaltener: Etwa vier von zehn (43%) geben an, dass sie dem gewählten Präsidenten Biden mindestens einen angemessenen Betrag für zuverlässige Impfstoffinformationen vertrauen, und ein ähnlicher Anteil (46%) gibt an, dass sie dem Präsidenten vertrauen Trumpf.

Die Gruppe, die sagt, dass sie definitiv nicht geimpft werden, ist möglicherweise am schwierigsten mit traditionellen Boten der öffentlichen Gesundheit zu erreichen. Sehr wenige sagen, dass sie den meisten Boten, die auf nationaler, staatlicher oder lokaler Ebene gefragt werden, viel Vertrauen schenken. Mindestens zwei Boten vertrauen nur der Hälfte der Menschen in dieser Gruppe: ihrem eigenen Arzt oder Gesundheitsdienstleister (59%) und Präsident Trump (56%), was darauf hindeutet, dass einzelne Heilpraktiker einer der einzigen Wege sein werden, um dies zu erreichen Gruppe mit genauen und zeitnahen Impfstoffinformationen.

| Prozent, die sagen, dass sie jedem der folgenden Punkte vertrauen much or eine angemessene Menge um zuverlässige Informationen über einen COVID-19-Impfstoff bereitzustellen: | Gesamt | Hol es dir so schnell wie möglich | warten wir es ab | Erhalten Sie es nur bei Bedarf | Wird auf keinen Fall bekommen |

| Ihr eigener Arzt oder Gesundheitsdienstleister | 85% | 96% | 87% | 82% | 59% |

| Die US-amerikanischen Zentren für die Kontrolle und Prävention von Krankheiten oder CDC | 73 | 89 | 78 | 68 | 26th |

| Die US-amerikanische Food and Drug Administration oder FDA | 70 | 86 | 75 | 66 | 26th |

| Ihr örtliches Gesundheitsamt | 70 | 84 | 76 | 67 | 28 |

| Dr. Anthony Fauci, der Direktor des Nationalen Instituts für Allergien und Infektionskrankheiten | 68 | 87 | 73 | 64 | 16 |

| Ihre Regierungsbeamten | 58 | 72 | 61 | 57 | 22nd |

| Gewählter Präsident Joe Biden | 57 | 77 | 62 | 43 | 14 |

| Pharmaunternehmen | 53 | 70 | 53 | 46 | 20th |

| Präsident Trump | 34 | 26th | 28 | 46 | 56 |

Comments are closed.